March 27, 2018

To Be A Happy Female Researcher

Prof. Michiko Kusunoki of the Institute of Materials and Systems for Sustainability, who retired at the end of March, was Nagoya University's only female professor of engineering. Once told by her own university teacher that she was "not single-minded enough," Kusunoki recalls: "I like this field and I somehow ended up continuing, rather than having a clear intention to continue." She had two breaks from research while bringing up her children, but was asked to return to work both times. She has achieved many years of successful research into new carbon materials like carbon nanotubes and graphene, moving to Nagoya University from a private research institute in 2007. In her final lecture, titled "Flexibly pursuing the production of nanocarbons," not "single-minded," she quietly talked about her eleven years at the university, and how much she had enjoyed working on research with the students.

After the lecture, she was presented with a bouquet of flowers on behalf of the female members of the engineering faculty by Associate Prof. Ayae Sugawara-Narutaki of the Department of Materials Chemistry, who thanked Kusunoki for supporting her junior colleagues, in a faculty where female teaching staff are in a tiny minority.

Kusunoki, who wrote a journal paper called "To Be A Happy Female Scientist" for The International Year of Chemistry in 2011, says she has always believed that showing she is happy in her research will encourage other women to follow in her footsteps.

Female teaching staff from the Graduate School of Engineering hold regular luncheons. There was nearly everyone to celebrate the retirement of Prof. Michiko Kusunoki (3rd from right on the back row).

Female teaching staff from the Graduate School of Engineering hold regular luncheons. There was nearly everyone to celebrate the retirement of Prof. Michiko Kusunoki (3rd from right on the back row).

Associate Prof. Ayae Sugawara-Narutaki is in front

After going to a girls' school in Shizuoka Prefecture, Kusunoki studied engineering at the Tokyo Institute of Technology (TIT). Most girls from her school went on to study arts subjects, so there was hardly any information available about universities for science subjects, but Kusunoki chose the university because she liked mathematics and physics. When she got there, she found it was just like a factory, and almost all the staff and students were male. She regretted her choice for a while, but finally felt a sense of relief in the fourth year when she was assigned to the electron microscopy laboratory and got her own desk.

She was intending to go back to her hometown and get married after graduating, but a senior member of the laboratory died and there was nobody to operate the electron microscope, so her teacher encouraged her to stay on and study for a doctorate degree. It was a hard decision, but in the end she continued her studies.

Her teacher, Prof. Shigemaro Nagakura, was the most understanding person towards women that she had ever met. His wife was also a researcher, and he had a natural awareness of gender equality. He also believed that getting a doctorate degree was important in forging a career, and indeed, Kusunoki's PhD opened up her future path.

After completing the doctorate course, she became an assistant in the same laboratory, but her husband was relocated to Nagoya, and going back and forth between the two cities took its toll; she was hospitalized for five months after a threatened miscarriage. Her son was born safely, and her teacher at the TIT asked her to come back to the lab. But the baby was so adorable, she did not want to go back to work after only one or two months, so she decided to devote herself to bringing up her child. She says she had to choose one or the other due to her own physical strength and abilities, but admits to sometimes feeling inferior because she was not more dedicated to her research.

After 18 months of "enjoying a carefree life of childcare," her teacher contacted her to say that electron microscopy researchers were needed for the "Ultra-Fine Particle Project" at the new Research Development Corporation of Japan (now the Japan Science and Technology Agency) opening at Meijo University, and told her to go for an interview. She was hesitant, having been away from research for a while, and that's when he told her she was "not single-minded enough." Reluctantly, she went to see the team advisor, Prof. Ryoji Ueda, professor emeritus of Meidai. He was a researcher she admired, world-renowned as a pioneer of electron microscopy. In the end, she agreed to join the team although declined working full-time, sending her son to nursery.

This project was a gathering of top researchers in the field of electron microscopy, including Chikara Hayashi, founder and chairman of Japan Vacuum Engineering, as a representative, and Sumio Iijima, known for the discovery of carbon nanotubes, who was called back from the U.S. to be on the team. Iijima later went on to discover carbon nanotubes from electron microscope images of iron particles made at this time. That such an unexpected major discovery could be hidden in a different direction from the original aim of the project is one of the fascinating aspects of research. Kusunoki calls it a "thrilling and enjoyable" time, being present for this historical discovery, and being able to research her own themes too.

When the project finished and her second son was born, she had another career break before becoming a researcher at the new Japan Fine Ceramics Center (JFCC) in Nagoya. Again, she worked on a part time basis while her children were young. During her experiments at JFCC, she discovered the structure of tightly packed rows of carbon nanotubes on the surface of silicon carbide (SiC). The objective of the experiment had been to heat SiC and observe the changes in the structure, but she found that at a high temperature of 2000 degrees, the silicon comes off, and for some reason, the carbon that is left forms a tube structure, lined up in regular rows. This was another unexpected discovery. She got a hint from Dr. Iijima, who mentioned at the researchers' New Year party that he was trying to align carbon nanotubes in the same direction. When she investigated the blackened test specimen under the electron microscope on the off-chance, that was exactly what he mentioned.

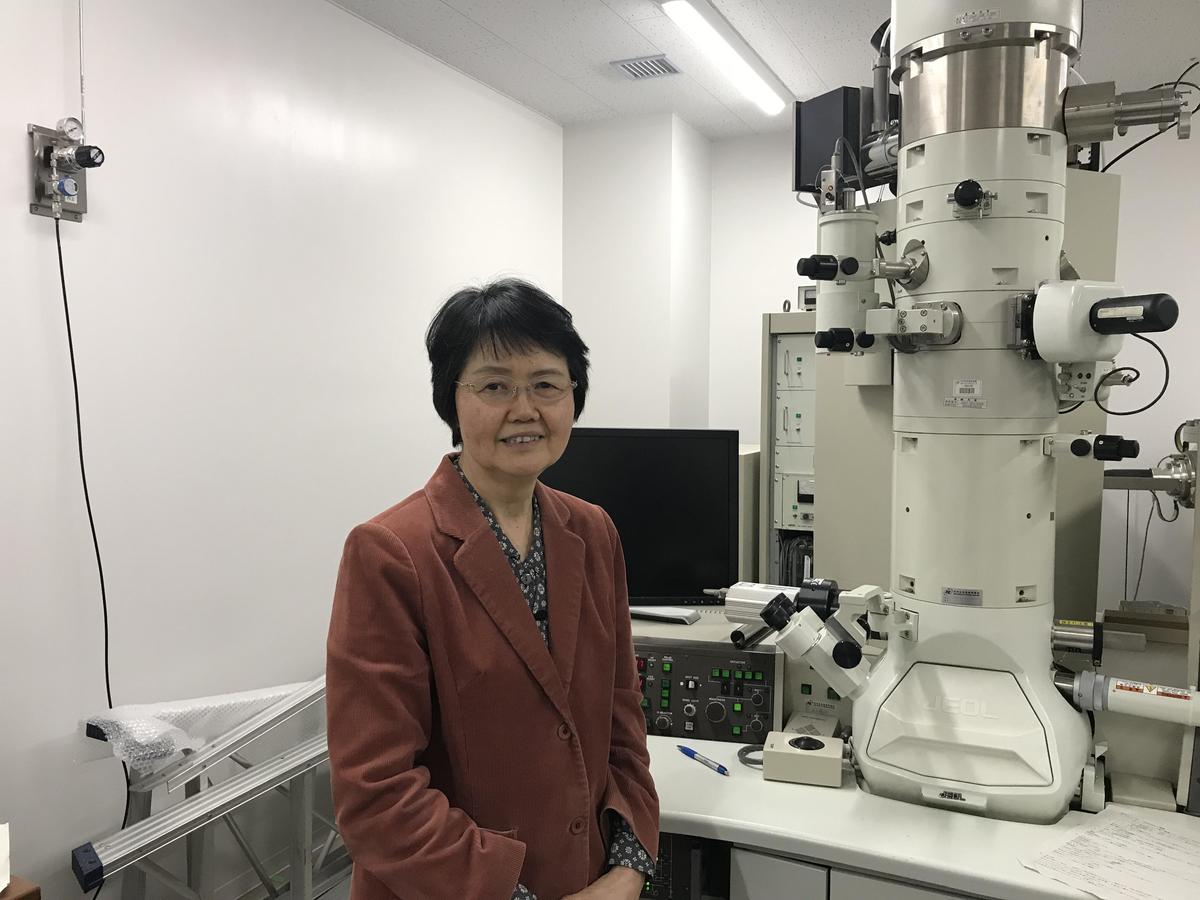

In front of her favorite electron microscope

In front of her favorite electron microscope

Carbon nanotubes are thousands of times finer than a human hair, stronger than steel, and conduct both heat and electricity, so they have great potential as a material for all kinds of applications. After moving to Meidai, Kusunoki carried on researching materials with special structures made from carbon, including graphene, and their applications. At the Center for Integrated Research of Future Electronics (CIRFE), which is part of the same research institute, a team led by Prof. Hiroshi Amano is researching power semiconductors using gallium nitride (GaN). SiC, the subject of Kusunoki's experiments, is also a power semiconductor material, so in that sense it is a rival to GaN, but she hopes that the continued development of SiC will have a ripple effect on other materials.

Kusunoki says that the biggest thing she has gained at Meidai has been her interaction with the students. Making samples in a high temperature oven, and taking images with the electron microscope: this kind of research requires students to be good with their hands too. She has seen the students starting in April, gaining skills by the time autumn comes around -- struggling, but persevering. When a study gets interesting, as she inspired students well, they become engrossed in research, steadily growing as scientists. Kusunoki says that seeing students develop in this way was the joy of being a teacher.

As for herself, she looks back on her fulfilling research career, and feels grateful to her teachers at the TIT who encouraged her to go on to the doctorate course, and the wonderful scientists she was lucky enough to meet on the Ultra-Fine Particle Project.

Now, she says cheerfully that she has "enjoyed research to the full." Electron microscopy requires massive research funding, and she feels it would be irresponsible to do it half-heartedly, so from April she intends to spend her time enjoying hobbies that have been shelved until now. "We're only halfway there in terms of results, but I will entrust the rest to the young people."

Sugawara-Narutaki, who presented the bouquet after the final lecture, also attended in an applied chemistry department meeting in the School of Engineering, which Kusunoki doubled as. She says there are considerations towards female staff, such as starting meetings at 3pm, making life easier for working parents. In other departments, it is not unusual for meetings to be held in the evening. Perhaps this is one sign of the female professor's importance.

Female researchers come in many different types, but Sugawara-Narutaki believes that seeing women like Kusunoki enjoying their research with a natural attitude will encourage others to think "I'd like to do that."

Kusunoki's ideas seem to have been passed on to her colleagues. Women often tend to avoid engineering, but in fact it is close to daily life in many ways. Compared to other schools, there are conspicuously few women in the School of Engineering, with no female full-time professors, and a total of eleven associate professors, lecturers and assistant professors, making up less than 4% of the total. I think seeing more and more happy female researchers is important for Meidai's School of Engineering, and indeed for the future of engineering.

Subscribe to RSS

Subscribe to RSS