March 22, 2019

Iwase Bunko Library and the Power of the Humanities

Nishio City's Iwase Bunko Library is currently holding an exhibition titled "There's a book like this!" The subtitle is "Iwase Bunko Heisei Comprehensive Survey Interim Report Exhibition 16". This is momentarily perplexing, but according to the explanation that deciphers it, the event is "the 16th edition of the fiscal year-end exhibition that provides a first look at rare and new books that have been discovered in the process of surveying the entire Iwate Bunko Library collection, which has been ongoing since fiscal 2000."

Iwase Bunko Library is a collection of mainly Edo-period antiquarian books assembled by local businessman Yasuke Iwase during the Meiji period, and it is renowned nationwide by those in the know. Since the year 2000, Professor Koh Shiomura from the Nagoya University Graduate School of Humanities has been reading through the entire collection of 80,000 books and creating a detailed catalogue. When Shiomura started out on the project he was amazed at the incredible books the collection contained, and close to 20 years later he says he is still surprised at what he discovers. Thus, every year he has organized an exhibition under the same title to introduce the newest survey finds.

What kind of books are "a book like this"? And how did they come to be preserved here?

The exhibition space at the Iwase Bunko Library

The exhibition space at the Iwase Bunko Library

Located in southern Aichi Prefecture on Mikawa Bay, Nishio City was a castle town of the Nishio Domain. Nationally, the area is a prominent producer of powdered green tea and regards itself as "Little Kyoto", but it is also "the town of books". Every autumn the Nishio Book Festival is held to develop regional culture through the power of books, with the aim of continuing the will and legacy of Yasuke Iwase. Incidentally, the domain of Chushingura villain Kira Kozuke-no-suke was located in Nishio City's present-day Kira-cho.

Upon exiting Meitetsu Nishio Station, you're greeted by a historic townscape where, in one corner, stands a vivid green cylindrical mailbox--an unusual sight these days. After continuing on, adjacent to the Nishio City Public Library stands "Japan's first antiquarian book museum", Iwase Bunko Library.

The unique thing about Iwase Bunko is that it has continuously been a library--since it was established in 1908, and as a municipal facility today--with the purpose of encouraging people to pick up and read old books. I want many people to read these books: that was the will of founder Yasuke Iwase. Thanks to the efforts of wealthy philanthropists, private libraries were established throughout the country starting in the Meiji period. Many collections, however, have been lost or destroyed due to things like disaster and war. It's nearly impossible to find an antiquarian book collection that not only still exists today, but where anyone can read what's inside.

On the right is the main building of Iwase Bunko Library, and the brown building in the center is the former archive

On the right is the main building of Iwase Bunko Library, and the brown building in the center is the former archive

The library itself is formed of the archive and a space for the general public, and in the reading room anyone over the age of 18 can view the books of their choice. First you must remove any watches, rings or other accessories from around your hands, put your belongings in a locker, and wash your hands. Then you wait for your requested book to be brought. Pens are not allowed, so any notes need to be taken with one of the provided pencils.

I requested a manuscript of the Ise Monogatari (Tales of Ise). Next to vivid paintings are handwritten lines of words that convey a feeling of energy. There are some lines that appear to have been written incorrectly then fixed, and there are traces of the letters being scraped away or erased with water. There were the people who wrote these words, and those who scanned them with their eyes. As I turn the page, I can't help but wonder how many others have done the same, and what kinds of people have felt their hearts beat faster as they perused those very same words. It feels as though I can even sense their breathing, and it's as if I share the same flow of time as those unknown readers before me through this single book.

In this way, books connect the thoughts of people over time. Digitized books don't do the same thing. It's what makes paper books special.

Professor Koh Shiomura working on the comprehensive survey. Most of his weekends are spent at Iwase Bunko.

Professor Koh Shiomura working on the comprehensive survey. Most of his weekends are spent at Iwase Bunko.

Shiomura is an expert on Saikaku Ihara and other early-modern literature. He knew Iwase Bunko well from his days as a student in Tokyo, but began visiting in earnest in 1985 when he took up a position at Nagoya's Sugiyama Jogakuen University Junior College. He continued to visit the archive when he moved to Nagoya University Graduate School of Letters in 1998. When Iwase Bunko was rebuilt in June 2000, a plan emerged for a "comprehensive survey" to make a detailed catalogue database available to the public, and Shiomura was chosen to lead the project. Comprehensive survey means you survey everything.

Looking back, he says, "It was the best thing I could have hoped for, just like a dream." Since then he has spent every weekend at the archive, as well as weekdays at the beginning, engaged in his work from 9am to 5pm. Many students and research colleagues also joined, and it has made for a valuable experience. As they go along, they publish detailed bibliographic data online, including an introduction to the contents of each book. They don't publicize digital images of the books, because they want people to come visit the library and actually hold the items in their hands. However, for a small number of particularly important works, the text is completely digitized and made searchable. Shiomura believes that, if someday all antiquarian books are digitized and researchable, it will change the humanities completely. He also works with the desire to pioneer the way into this era.

An example of a "book like this" he has found during the survey is the Zokushigusho. This is a lengthy scroll written based on various documents that details happenings in the imperial court and beyond during more than 500 years, from the Kamakura period (1185-1333) to the middle of the Edo period (1603-1868). The surprising thing is that nobleman Yanagiwara Motomitsu wrote the entire thing by himself, with help from his family. History specialist and curator Takanori Murase says that he is overwhelmed by Yanagiwara's feat. It's a valuable historical text widely known amongst historians, and survives in nearly perfect form at the Iwase Bunko Library.

Other items in the collection span a truly wide variety--from geographical texts on each region of the country to the reading record of a book-loving daimyo (feudal lord), dog breeding manuals to illustrated books of animals and plants--and teaches us in detail about life, society, and disaster in the days of old. There are many times when Shiomura is really amazed what kinds of records were left and preserved. He says Iwase Bunko's collection of books about Mt. Fuji is the largest in Japan.

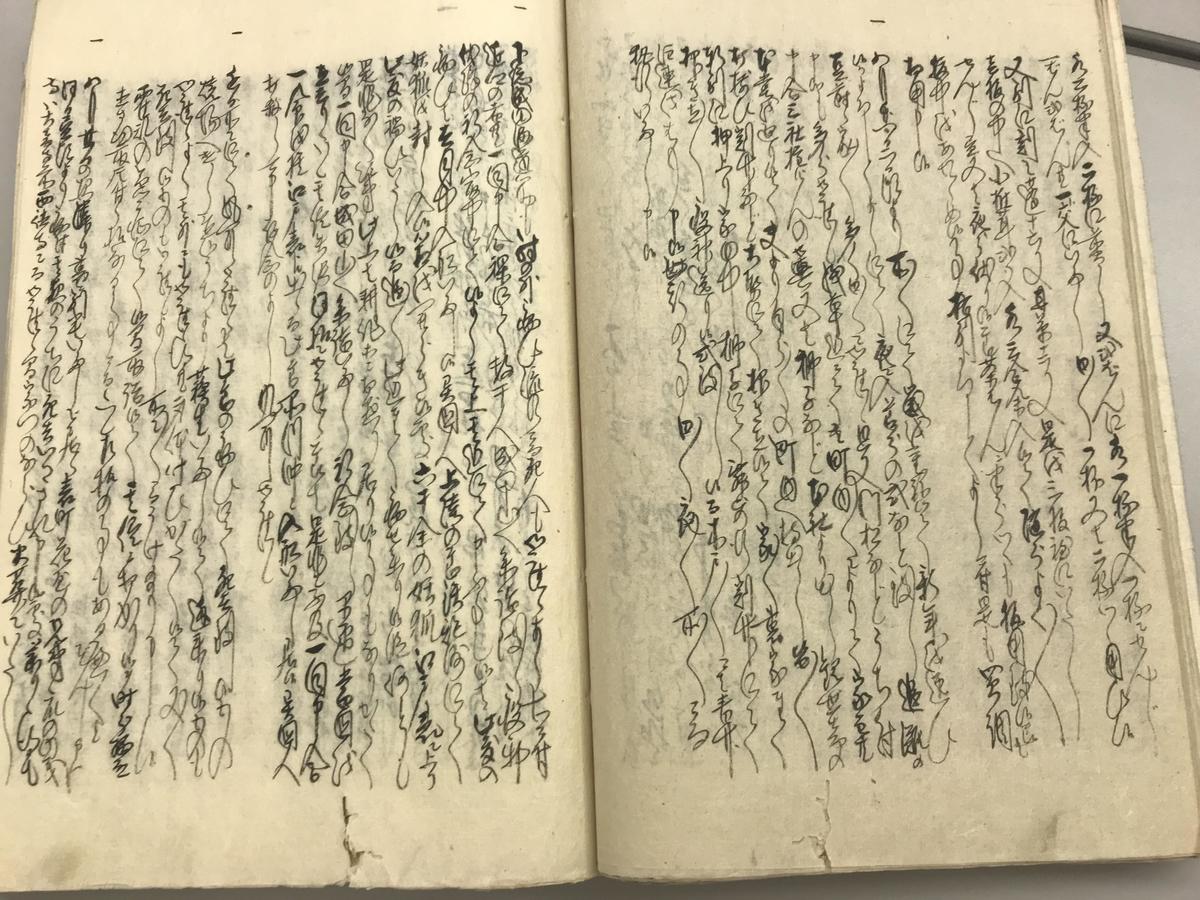

The Atomukashi Anzen-roku tells in detail about a major earthquake

The Atomukashi Anzen-roku tells in detail about a major earthquake

The survey is nearly finished, and Shiomura says he is now working on the remaining little bits and bobs. This edition of the exhibition is full of the "extra extras", meaning works he really wanted to include in previous editions but reluctantly had to leave out. At the beginning of February I went to see the survey before the exhibition opened, and was shown a memoir of disasters titled Atomukashi Anzen-roku. It is a detailed record of things like the Ansei Edo earthquake (1855), as well as the cholera and measles epidemics of the time. The author is said to have been a merchant living in Edo's Minami-honjo Banba-machi, who was 40 years old at the time of the quake. He provided a truly riveting description of being caught in the disaster: At 10pm, he had just laid down to sleep when "a rattling noise came from the ceiling". He took his newborn son in one arm and rushed to the next room when "there was a creaking noise and the house fell on my head." "It's a superb piece of reportage literature, with a description that gives a strong sense of presence," says an astonished Shiomura. It's the many single unique copies left behind by ordinary individuals that make Iwase Bunko special.

Atomukashi Anzen-roku is displayed in the first part of the exhibition on "old books about daily life in Edo". The exhibition is split into five parts, four on different regions and people followed by a fifth on "curious old books that appear one after another", which features collections of gossip and strange stories, genre paintings at the time, and others.

The “Yasuke lantern” at Ibun Shrine inscribed with the will of Yasuke

The “Yasuke lantern” at Ibun Shrine inscribed with the will of Yasuke

What kind of person was Yasuke Iwase? He was born in 1867, just before the dawn of the Meiji Era, and made his fortune through the family fertilizer business. He had always been an avid bookworm, but apparently began collecting old books after being inspired by Masaka Watanabe, one of the most prominent intellectuals in the region of the late Edo period. Masaka declared, "People all have their differences in what they consider treasure, but the one thing that is essential to man is books," and when he established his own modest book collection and opened it to the public, he wrote, "Things should be shared to enjoy with everyone. Let's also read books together, and improve ourselves daily." He also spoke of the significance of books and how, without them, we could never pass down the events of the past to future generations. In Shiomura's book, Mikawa ni Iwase Bunko ari (Iwase Bunko is in Mikawa), which introduces the collection, he points to the idea of Masaka as being the essence of libraries, and writes, "As far as books go, there is just something tremendous in the culture of Mikawa."

Yasuke spent his money devotedly collecting Edo-period books from antiquarian bookstores in Tokyo, Kyoto, and elsewhere around the country. The appeal of Iwase Bunko, says Shiomura, is that there are a number of valuable books that can't be found elsewhere, and it contains almost no duplicates, probably because Yasuke collected books with a specific intention. Iwase Bunko has been in danger a number of times--like when it was damaged in the 1945 Mikawa earthquake, or when it was sold off to reduce inheritance tax--but after pressure from locals to protect a regional treasure, it has now been purchased and is maintained by Nishio City.

Yasuke almost never spoke about himself, but one can infer his intentions when looking at the inscription on a giant stone lantern at nearby Ibun Shrine. "I once established a small library for both myself and the people, and want this to be forever continued." By making this personal collection public, local people have protected the library even after Yasuke's death, giving it an everlasting existence. These are the fruits of the noble ideas passed down by Masaka.

As seen in the examples from Iwase Bunko, many of our forefathers, both famous and not, have left behind a variety of written works. "Japan is exceptionally abundant in books," says Shiomura. It is then unfortunate that we forget about this in our daily lives. Isn't it essential to maximize this resource--in other words, to enrich our current lives by digging up and applying the knowledge of the past? It is said that today is "the era of regional development", but our local regions once had rich cultures and the capability to leave these kinds of books behind. The ultimate "era of regional development" has already happened. And if that is the case, then we should listen closely to what our ancestors thought and how they lived.

Shiomura says that reading these kinds of books can help strengthen our imaginations. We can strive to understand, more extensively and more deeply, the way our ancestors lived by really using our imaginations. And then we must think carefully about how to tell others about the things we've found. This is how we hone our strengths as humans. Strengthening the power of our imaginations and our humanity is, indeed, also what studying the humanities is about.

The Nagoya University Academic Charter states the university's objective to "foster individuals who possess intellectual courage, the power of rational thought, and imagination." Naturally, it's not only the humanities that demand imagination. It is indeed necessary within the sciences, which have the potential to greatly change society through technology. These days the humanities tend to be looked down upon, but we need to reconsider their role within the university. If this is not done, it would be inexcusable to our ancestors who created written work and left it behind for us.

The exhibition runs till April 14th.

Subscribe to RSS

Subscribe to RSS