September 27, 2019

Thinking About Cars in Nagoya

"Cars are endlessly fascinating from a cognitive science perspective," says Professor Kazuhisa Miwa of the Nagoya University School of Informatics and Sciences. Cars have been a powerful tool, giving humans freedom through mobility. We find it completely ordinary, but the act of driving cars actually requires sophisticated cognitive abilities, such as sensory perception, memory, and motor control. Driving can also present life-threatening risks. Turning on a blinker is way of signaling one's actions beforehand, an unusual behavior. In other words, the act of operating a car is a rather special thing, but rarely are we aware of it as such when driving. Special yet ordinary. What a peculiar tool.

So how will the much-talked-about autonomous driving change all this? If your view of the future is rose colored, Miwa, it turns out, thinks otherwise. "It won't necessarily make drivers happier," he says.

The Global Research Institute for Mobility in Society (GREMO), which opened last April and held its inaugural symposium in late July, belongs to Meidai's Institutes of Innovation for Future Society and has a vision for "Human Centric Mobility." Nowadays, discussions about automobiles are often prefaced with the phrase "once-in-a-century transformation." Indeed, experts from various fields, in addition to automotive engineering, are coming together to address the challenges --with cars and beyond -- of using emerging technologies in ways that lead to a genuinely higher quality of life. Miwa is one such expert. When I visited the institute, I discovered that such challenges are dizzying in number. And none are easy to solve.

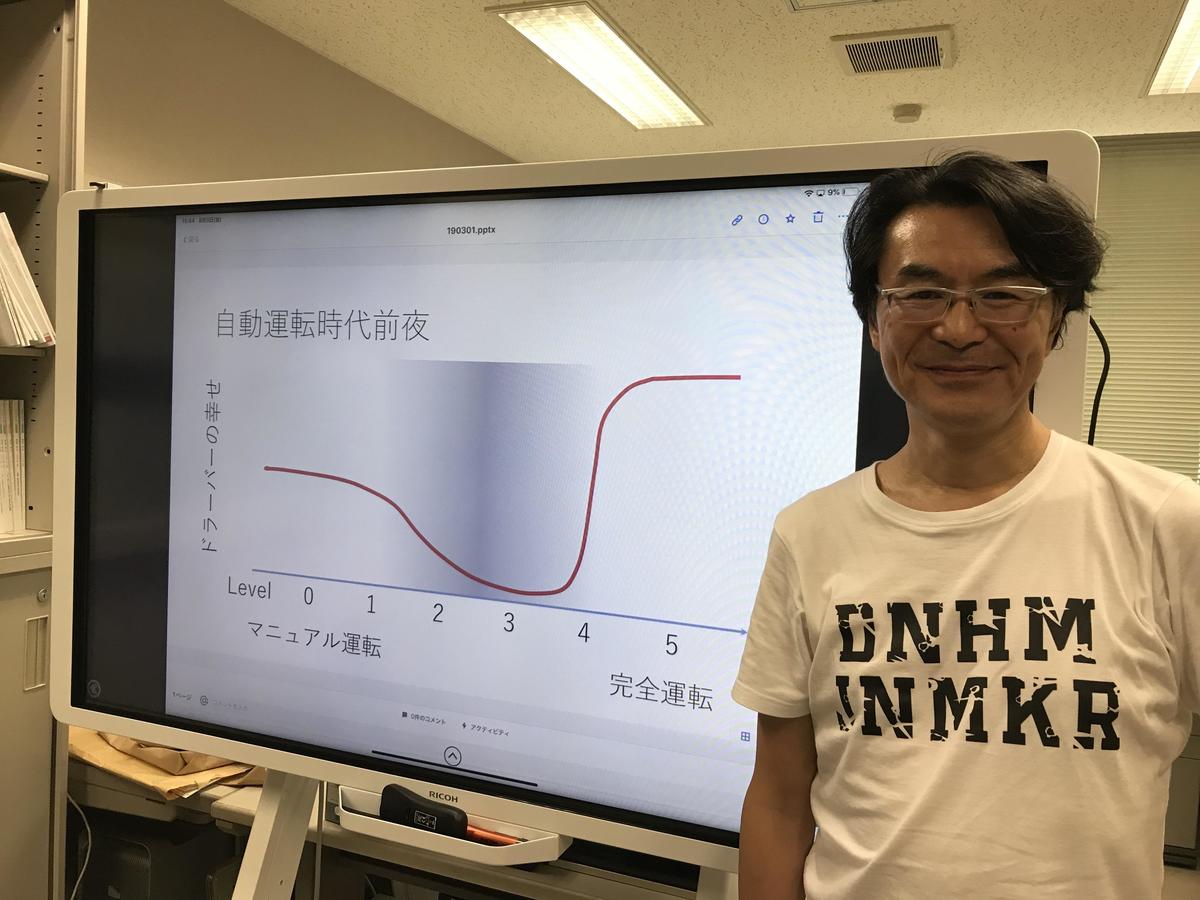

Prof. Kazuhisa Miwa presents a graph of driver satisfaction

Prof. Kazuhisa Miwa presents a graph of driver satisfaction

Miwa presented a graph showing driver satisfaction on its vertical axis and level of autonomous driving on its horizontal axis. Level 1 and 2 make up the phase called "driving assistance," where the vehicle assists operation of the steering wheel and brake. In levels 3 and 4, autonomous driving is possible in certain places, such as highways, though humans must intervene in emergencies in level 3. Level 5 is the fully self-driving car, where no human intervention of any kind is necessary; the vehicle doesn't even have a steering wheel, gas pedal, or brake. According to the graph, driver satisfaction is lowest at level 3.

Machines are meant to help humans, but in level 3 the relationship is flipped: human must watch and help machine. It's a reversal of roles between server and served. This phase could even be dangerous, as humans, their hands and minds now idle, will tend to suffer a loss of driving ability and attention, and suddenly will have to cope with a certain situation. This is far from satisfactory. Only at level 5 does satisfaction jump upward.

The level of autonomous driving does not mean that it goes step-by-step. Negative views of level 3, where the burden on drivers is greatest, are not uncommon. Google, for example, aims to skip this step and jump straight to fully autonomous driving.

Even if level 5 were attained, however, there will still be people who want to drive, leaving the issue of harmonizing their vehicles with fully autonomous ones. There's a possibility the two types will behave differently, such as when changing lanes or passing. It's crucial that they can drive together naturally. "As machines become more advanced, the human factor becomes more important," says Miwa. Another challenge, he says, is how to use advanced assistive technologies so that they enhance rather than diminish human abilities.

One of Prof. Takayuki Morikawa’s roles is overseeing demonstration testing of autonomous vehicles

One of Prof. Takayuki Morikawa’s roles is overseeing demonstration testing of autonomous vehicles

Meanwhile, a different set of challenges is being raised in the field of civil engineering, which has deep societal relevance. If cars change drastically, and if we are going to use them skillfully, road environments and rules will also need to change. The great number of cars in society is another defining characteristic of automobiles. Changes in how cars travel could even impact how we live and build communities.

Takayuki Morikawa, professor of civil engineering, is investigating the impact of autonomous driving on traffic systems. Autonomous vehicles might move slowly and disrupt traffic when performing certain tasks, such as making a turn through opposing traffic, so he's running simulations to understand what happens when such cars reach certain thresholds. At 30% of traffic, it's probably more efficient to create a dedicated lane, he says. Additionally, the arrival of something like robotaxis, fully self-driving taxis, could have unexpected results. A decline in vehicle ownership is likely, but if convenient and cheap enough, their rise in use could also bring major congestion and cause public transit systems to fail. In Japan, this could draw people away from downtown and into suburban areas, counteracting moves toward compact cities in an age of population decline.

"We must take steps now based on a long-term vision of mobility that also considers things like environmental impact and social equity, so that everyone can benefit from the freedom it provides," says Morikawa.

Another buzzword when talking about cars is CASE, or "connectivity, autonomous, sharing, electrification." Efforts have also begun in the area of MaaS, connecting all modes of transport to provide Mobility as a Service. With MaaS, vehicle ownership will no longer be the mainstream choice for individuals. In just 20 years' time, the automotive industry may shift structurally and become a mobility service industry, a view of the future that has inspired IT companies to undertake their own bold ventures.

But Morikawa sees it differently: "The circumstances surrounding mobility won't be entirely different in 10 or 20 years." The debut of the Ford Model T in 1908 was truly revolutionary, bringing mobility to individuals who had none before. The changes this time won't be quite so drastic. But major changes will come, which is why it's important to be prepared for the long run.

These are just a few example from a truly wide range of research themes currently underway at GREMO. Another is focused on thinking more broadly about information services, in mobility and beyond, and understanding how safe they have to be to be accepted by society.

Prof. Kazuya Takeda is passionate about management. “I want to move research forward with my young colleagues,” he says.

Prof. Kazuya Takeda is passionate about management. “I want to move research forward with my young colleagues,” he says.

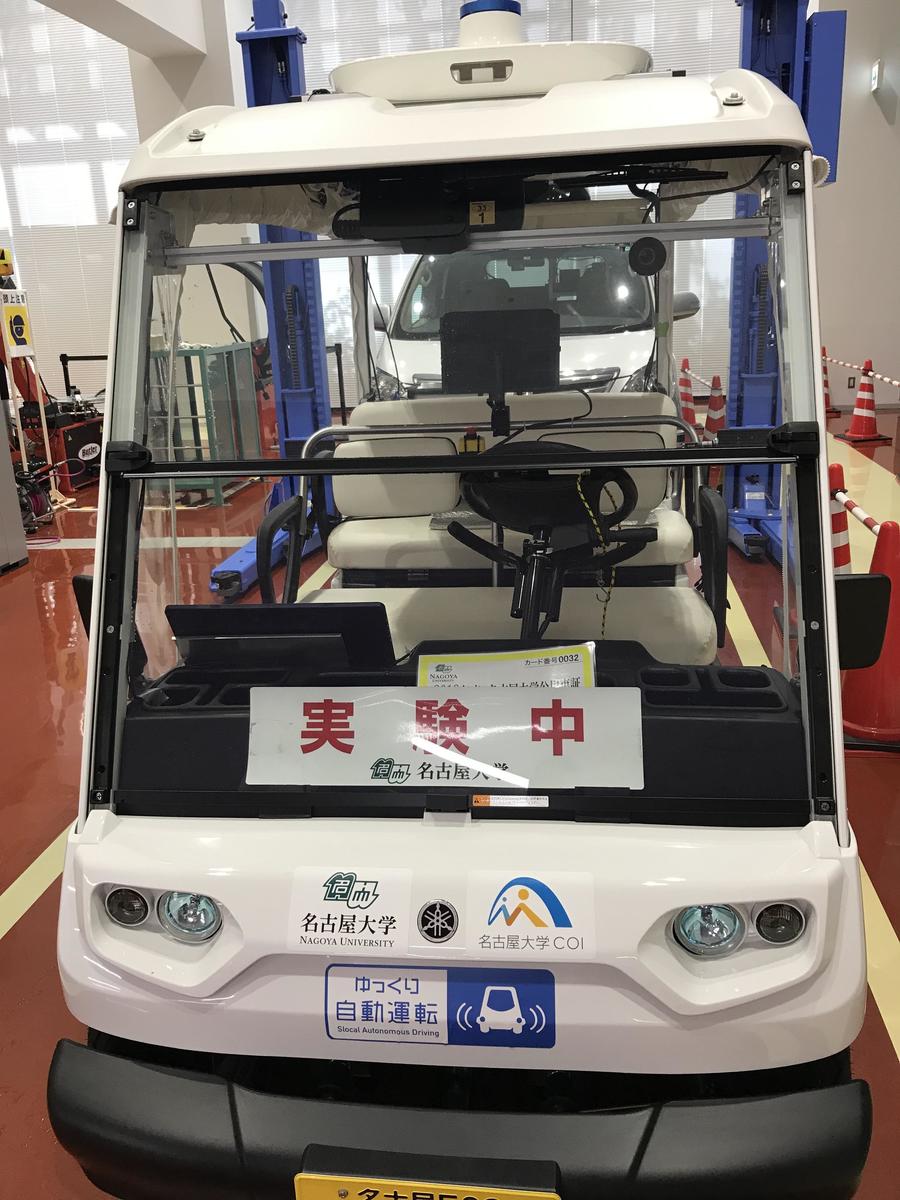

When it comes to cars, though, Meidai is actually a well-known entity in the autonomous driving world. That's because Autoware, a software platform for self-driving developed by Tier 4, a startup spun off of research at Meidai in December 2015, is available for free and used around the world. Any car can be made autonomous simply by installing the software onto the car's computer, as long as it meets certain system requirements, such as sensors for monitoring the exterior environment.

The software was developed by Shinpei Kato, who at the time was associate professor in the Nagoya University Graduate School of Information Science. The software is like a computer operating system, and Kato adopted the strategy of making it open source, available to use by anyone for free. The strategy paid off, finding users around the world and attracting some 12.3 billion yen in investment from companies and others. Kato moved to the University of Tokyo in April 2016, and now sits on the executive board at Tier 4. Last December he founded and became board representative of the Autoware Foundation, a non-profit organization supporting open-source projects that will enable self-driving mobility. More than 40 companies worldwide, including a Toyota R&D firm, semiconductor manufacturers, and telecom companies, are members and working to make Autoware the global standard. Their rival is Apollo, software developed and promoted by Chinese search giant Baidu.

The president of Tier 4 is Professor Kazuya Takeda, who supported Kato in starting his research on self-driving software when Kato was assigned to Meidai after returning from the US. Takeda, who also serves as deputy director at GREMO, then specialized in audio signal processing, but has since expanded his field of interest to behavioral signal processing, which seeks to understand human behavior through an analysis of behavioral data, and to the development of self-driving systems that can understand and respond appropriately to human states and intentions.

It was Miwa, mentioned at the top of the article, whom Takeda invited in the hope of understanding human better. Miwa was the perfect partner: a younger alumnus from the same high school and, as a cognitive scientist with a background in engineering, one who can speak the same language as Takeda.

"In ten years, the world of technology will be much changed. I want to foster people who can pioneer that change and imagine technology's impact," says Takeda.

A self-driving test vehicle under development at Meidai

A self-driving test vehicle under development at Meidai

Professor Tatsuya Suzuki, executive director of GREMO, specializes in system control engineering and likewise has a long-standing connection to autonomous driving. Around 2000 when he was in the US, autonomous driving was in vogue and highway driving tests were common. The research fizzled out, however, when they couldn't solve certain issues, such as merging on local roads. With that experience in mind, Suzuki expects the technology still has a number of swings to go through.

At GREMO, Suzuki hopes to promote research in line with its institutional vision of human-centric mobility systems, and also produce researchers who can translate academic value into social value.

So what does the future hold? When it comes to mobility, there's a gap between the future painted by the IT industry and realistic projections. It's the diversity of such perspectives that's key.

The social and economic importance of the automobile goes without saying. It's not too farfetched to say that if cars change, society, and the world, will change. There are many problems that need to be addressed, with cars themselves as well as areas beyond them, problems that are certainly not unrelated to automotive technology. These are issues that Meidai, an automotive engineering mecca situated in the Tokai region, where automotive and related industries are heavily concentrated, should tackle as a liberal arts institution. Industry is looking to Meidai, with its insights in cognitive science and other disciplines, for help in solving them. Suzuki himself wants to involve researchers in the social sciences and humanities as well as engineering in this effort.

Thinking about cars and mobility in Nagoya, I'm excited about what's yet to come.

Subscribe to RSS

Subscribe to RSS