In the middle of March, a ceremony to commemorate the naming of nihonium was held at the Japan Academy in Ueno, Tokyo, to officially declare that the new element 113--synthesized for the first time at RIKEN--would be named "nihonium." ("Nihon" is how Japanese pronounce their country's name.) This marks the first time since Dmitri Mendeleev published the periodic table of the elements in 1869 that an element created in Asia is being listed on the table, which had been populated by European and American efforts. That makes this a truly historic event. I was able to attend the ceremony, which triggered many thoughts for me.

The first thing that occurred to me was that if the element had been synthesized just a bit sooner, the name nihonium would probably have been declared by a Japanese person. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC)--which could be called the United Nations in the world of chemistry--is responsible for the naming of new elements, and the current president is Prof. Natalia Tarasova, D.I. Mendeleyev University of Chemical Technology of Russia. Two terms ago, from 2012 to 2013, the president was Designated Professor Kazuyuki Tatsumi of the Research Center for Material Science at Nagoya University. On the day of the ceremony, he was watching over the proceedings as a member of the Japan Academy.

"It was so close." Comments like this were heard in the room. Through experiments the element was created in July 2004 and April 2005, and then, seven years later in August 2012. Eventually the achievement was recognized with the IUPAC announcement on New Year's Eve in 2015 that the RIKEN group would get the naming rights for the new element. As a result, the congratulatory news ended up on the front page of newspapers on New Year's Day. However, Prof. Tatsumi's role as then-president went to the end of 2015, so the unusual timing of the announcement on New Year's Eve was apparently an attempt to do something before his term ended.

At the celebration, research group director Kosuke Morita introduced his colleagues, referring to the work of his 48-person team (March 14, 2017, at Tokyo National Museum )

At the celebration, research group director Kosuke Morita introduced his colleagues, referring to the work of his 48-person team (March 14, 2017, at Tokyo National Museum )

Could this all have come a little sooner? Let's look back on the events leading up to this day. The elements that exist in nature go up to atomic number 92 (uranium), and everything from element 93 and above can only be synthesized artificially. Since the atomic number is the number of protons in the nucleus, a specific atomic number can only be created by forcing nuclei to collide against each other to reach that exact number. It may sound simple, but this involves extremely small things interacting with each other. They do not easily collide, and they do not combine easily. A relatively strong force is required to make them collide, but if it is too strong they will not be synthesized. On top of that, it takes a tremendous number of repeated experiments, and one can only wait for the good fortune of having the particles synthesize for you.

It was in 2003 that the team under RIKEN research group director Kosuke Morita started the experiment, and they were able to create one atom the next year, and another one the year after that. But the atoms survived just two-thousandths of a second, as they decayed quickly and transformed into other elements. They submitted reports that element 113 had been created, but more data was needed. Then they had no further success for more than seven years. This must have been a painful wait, though Morita said "I was confident we would do it." At the ceremony he reflected on how it felt the moment when it happened: "'It came!' was my only thought." In the end, after 400 trillion collisions only three atoms were created, and that is such a small probability it could make one's head spin.

If the third atom had been created and recognized more quickly, there is a good chance it would have been Prof. Tatsumi making the declaration as president. On the other hand, there is also the possibility that it could have taken very much longer. For research into the unknown, it is probably typical when things do not go as you might wish. In fact, Russian and American research groups had already claimed that they had created element 113 using different methods, but having created the third atom was the powerful evidence that earned the naming rights for the Morita group. In the end, the more than seven years of effort had not been lost.

Prof. Tatsumi says that it was then-president Ryoji Noyori and other top people at RIKEN who had supported the effort for the seven years despite producing no results. Prof. Morita is also a professor at Kyushu University, but Prof. Tatsumi says it would have been very difficult for the work to continue at a university. The question of how to support basic research, which often does not produce immediate results, is an important topic for now and the future.

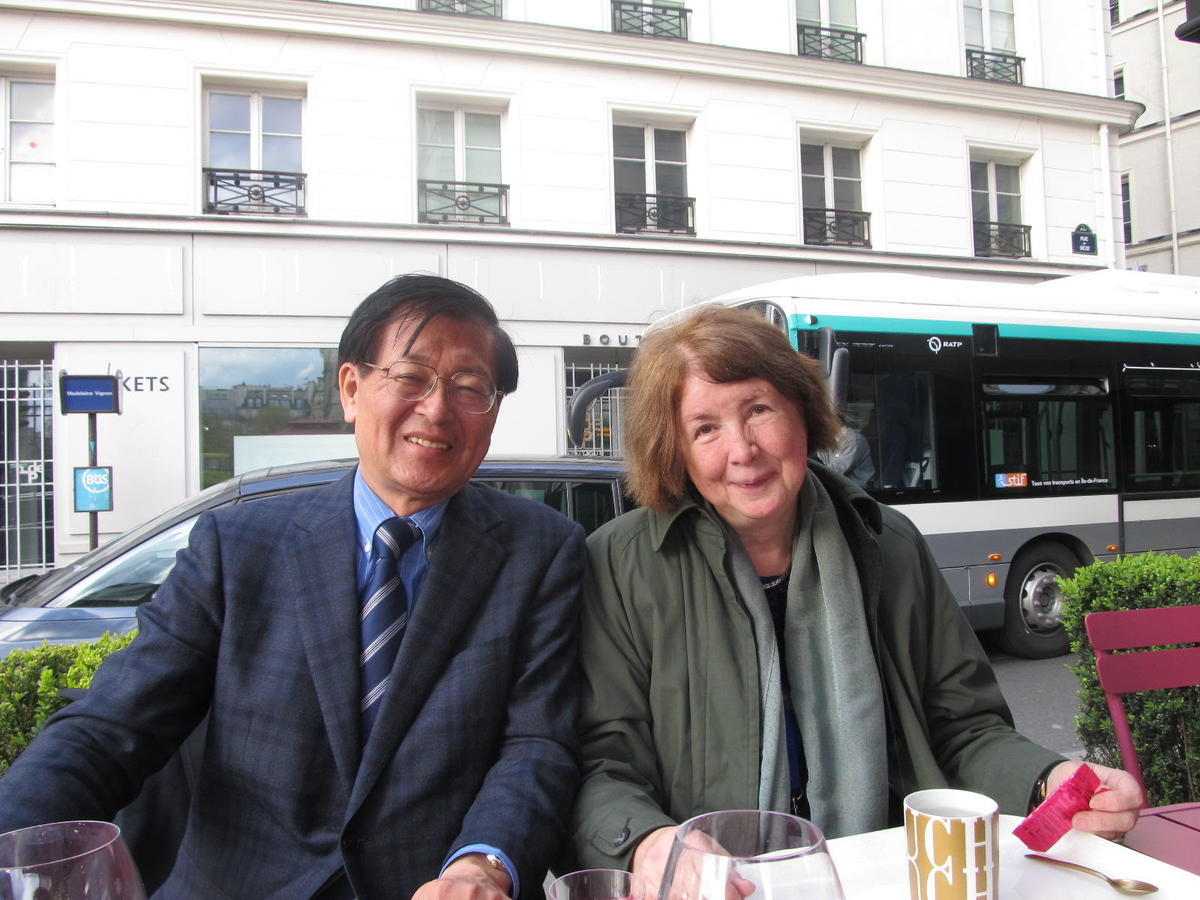

IUPAC President Natalia Tarasova (right) with former President, Designated Professor Kazuyuki Tatsumi, of Nagoya University (Paris; photo provided by Prof. Tatsumi)

IUPAC President Natalia Tarasova (right) with former President, Designated Professor Kazuyuki Tatsumi, of Nagoya University (Paris; photo provided by Prof. Tatsumi)

At the ceremony, His Imperial Highness the Crown Prince addressed the attendees, recalling the impression made upon him from having to write out the periodic table of the elements more than 30 times by hand as part of his summer homework in high school. Next, IUPAC's President Natalia Tarasova, Bruce McKellar, president of the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP), and Yuri Tsolakovich Oganessian, Scientific Leader, Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, Russia, also attended and gave congratulatory addresses. IUPAP and IUPAC jointly recommend the members of the joint study committee that investigates who was the first to create a new element. Chemistry is what utilizes the periodic table, but the synthesis of elements is done through physics experiments, so it is necessary to have physics experts involved. Both presidents are very busy, so they attended the event on a quick schedule, with only a day or so in Japan. Prof. Oganessian is a renowned personage in the world of elemental synthesis, having been involved in the naming of three new elements besides element 113 this time. Element 118 (oganesson) even bears his name. This event had a lineup of individuals that made one sense the real significance of having a new element being added to the periodic table.

President Tarasova spoke rather poetically, saying that chemistry is the music of the natural world, that the music is played with a finite number of elements to create the infinite beauty of the universe. She also touched on Japanese culture, referring to the wonderful expression ka-cho-fu-getsu (literally flower, bird, wind, and moon), meaning to enjoy the beauty of nature and in so doing to learn about oneself. Then, as IUPAC president, she formally declared nihonium as the name of element 113.

The next congratulatory addresses were from Japanese invitees, but with the exception of the president of the Japan Academy, statements were read out on behalf of officials who were not present: the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, the Minister of State for Science and Technology Policy, and the President of the Science Council of Japan. Besides the fact that parliament was in session, they must have had their own reasons for not attending, but their absence was unfortunate. Statements that the Government of Japan is committed to science and technology rang hollow.

Japan has a history of research into new elements. Masataka Ogawa announced in 1908 while studying in England that the new element he had discovered and named nipponium corresponded to element 43 on the periodic table, but it was later learned that this was actually the as-yet-undiscovered element 75. It was indeed a new element, but because the place on the periodic table was wrong, the name nipponium did not remain. It is said that he later continued to conduct research while serving as president of Tohoku University.

Then, using the first cyclotron ever built in Japan in 1937, Yoshio Nishina of RIKEN discovered uranium 237, which should decay into element 93. But he could not identify element 93 in that decay, and naming rights for element 93 were later given to an American group. Dr. Nishina is also recognized for having trained both Hideki Yukawa and Shin-itiro Tomonaga, who both earned the Nobel Prize.

The speeches by pioneers at the ceremony brought back my memories of the words of His Majesty the Emperor of Japan in June 2007 at the opening ceremony of the International Nuclear Physics Conference 2007 in Tokyo. After the war, Dr. Nishina's cyclotron was dumped into the ocean by the GHQ (the offices of the occupation forces), but the Emperor recalled his own tour of a new superconducting ring cyclotron prior to its start of operations in the fall of 2006, and said with feeling, "I can imagine how painful it was for Dr. Nishina when the first cyclotron ever built in Japan was dropped into the ocean after the war." The Emperor, who is himself a biology researcher, alluded to both the bright side and dark side of scientific progress, and concluded by saying that he hoped it would contribute to world peace and the happiness of humanity. His words left a deep impression on the attendees of the ceremonial address and they were later published in an international scientific journal.

If the Emperor were to have seen the ceremony this March, I could not help but imagine that he would have felt sadness for Dr. Nishina but also feel profoundly pleased with the achievements of his successors. With the current Emperor's abdication approaching he is seeing a reduction of public duties, but if this naming of a new element had happened a few years ago, would there have been an opportunity for him to be present at the ceremony?

Kazuyuki Tatsumi, then-president of IUPAC, declaring naming of the new element livermorium at ceremony in Moscow (October 2012; photo provided by Prof. Tatsumi)

Kazuyuki Tatsumi, then-president of IUPAC, declaring naming of the new element livermorium at ceremony in Moscow (October 2012; photo provided by Prof. Tatsumi)

As for the future, will there be an opportunity for a Japanese president of the IUPAC to declare the name of a new element that has been synthesized in Japan? The IUPAC was established in 1919, just after World War I as the world reflected on the calamity of war, with aim of promoting scientific advancement through international collaboration from both the scientific and industrial perspectives. According to Prof. Tatsumi, Japan was active in the IUPAC immediately after it was established. From 1928 to 1930: Joji Sakurai, described as the cornerstone of modern science in Japan, served as vice-president, and that was probably a sign of the recognition of capabilities in chemistry that Japan already had at the time. As for the role of president, Saburo Nagakura also served as president from 1981 to 1983, so that means there have been only two Japanese presidents in nearly 100 years of the organization's history. In 2012 when the naming ceremony was held grandly in Russia for element 114 and element 116, it was President Tatsumi who made the announcement. The term of president is two years. Before Prof. Tatsumi, the role was held by Prof. Jung Il Jing from Korea, and after the current president from Russia, the next will be Prof. Qi-Feng Zhou from China. For Korea and China, this is the first time to provide presidents, a noticeable sign of advancing competence in Asia.

Meanwhile, for the synthesis of new elements, Russia and the United States have traditionally worked in collaboration. Among three other elements recently named in addition to element 113 this time, other than element 118 (oganesson) mentioned above, moscovium (element 115) and tennessine (element 117) bear geographical names from Russia and the United States. In recent years, Germany has also been putting an effort into this field, and new elements with geographical names like darmstadtium (element 110) have appeared. This is the context into which Japan has entered the scene. The competition to synthesize even heavier elements is growing more intense.

Perhaps it is not a just dream that one day a Japanese president of the IUPAC will declare the name of a new element that has been created in Japan.

Subscribe to RSS

Subscribe to RSS