December 28, 2017

Are Law Scholars Disappearing?

This past fall, an event was held at the Hanoi Law University in Vietnam to mark the 10-year anniversary of the foundation of the Nagoya University Research and Education Center for Japanese Law (CJL), an institution that provides Vietnamese students an opportunity to study Japanese Law through the medium of the Japanese Language. The program is popular but tough to complete, since it must be taken in addition to the full degree curriculum delivered by the School of Law of Hanoi Law University. Every year, over 200 students apply for 25 places; only 10 or so successfully graduate. If it is difficult to get in, it is even harder to get through to the other end. So far the Center has produced 71 graduates, of whom 22 have gone on to postgraduate studies at Meidai and other Japanese universities. Others are working for a wide range of employers including Japanese companies, universities and government agencies in roles that link Japan and Vietnam.

Minister of Justice Le Thanh Long, who gave a congratulatory speech at the event, also learned Japanese Law - on an English language program as it was before CJL was established - and went on to complete his doctorate at Meidai. In his speech, he attributed his success to his studies at Nagoya University and praised CJL for nurturing talents who will build a bridge of friendship between Vietnam and Japan. The President of Meidai, Seiichi Matsuo, attended the ceremony alongside Dr. Le Tien Chau, the Rector of the Hanoi Law University, both of whom vowed to continue expanding the Center's success.

People attending CJL's 10-year anniversary event held at the Hanoi Law University, November 15, 2017

People attending CJL's 10-year anniversary event held at the Hanoi Law University, November 15, 2017

The event was a timely reminder of the solid success of the Meidai School of Law's effort to provide legislative assistance to Asian countries and train human resources (http://www.meidaiwatch.iech.provost.nagoya-u.ac.jp/en/2017/02/post-1.html) and to teach Japanese law in Japanese (http://www.meidaiwatch.iech.provost.nagoya-u.ac.jp/en/2017/05/51.html). It is ironic, then, that the Nagoya University School of Law itself is apparently facing a crisis in its own human resource development. "The system for training academics has all but collapsed," according to Professor Emeritus Akio Morishima, who also attended the event. A Civil Code specialist and a former Dean of the School of Law, he pioneered Meidai's legislative assistance initiative in Asia. Can the Meidai School of Law continue to meet the rising Vietnamese partner's expectations? Upon my return to Japan, I visited the School of Law to find out.

The School of Law offers 150 undergraduate places under the banner: "small school, diverse program." At one point, around 100 academics from Meidai taught at universities across the country.

The School of Law offers 150 undergraduate places under the banner: "small school, diverse program." At one point, around 100 academics from Meidai taught at universities across the country.

What's behind this problem is the law school system, an American-style JD degree program introduced in Japan in 2004. The government hoped that it would boost the number of legal professionals such as lawyers and judges, but the demand stagnated. The loose standard applied to the approval of these new law schools meant that law exam pass rates among their graduates were low, and the number of applicants declined. Many universities are forced to close their law school altogether. The policy has clearly failed. At the height of the rush, 74 law schools were set up; almost half of them - 35 schools to be precise - have either closed or stopped taking in new entrants by this summer. Even well-known private universities weren't immune, and these high-profile casualties frequently made the news, but this failure had more serious consequences. The system of training academics - people who teach at universities - has collapsed, and this problem is threating the very existence of the school of law.

How did this happen? Creating the new law school was a huge undertaking - it required the level of resources needed to create a brand-new faculty from scratch, but no extra buildings or human resources were made available. To overcome this problem, universities sacrificed associate professor posts. These posts had previously been used to remunerate fledging scholars who had just received their doctorate and were embarking on a career in research. The norm used to be that new researchers would spend around a decade in these posts while working on papers and studying abroad to gain enough scholarly experience. Now that these posts are gone, students who have completed their doctorate have nowhere to go.

The truth is that the number of law graduates continuing postgraduate study with the aim of joining academia had already been shrinking. Law is not the only discipline affected either; the decline in postgraduate enrolment is seen across academia, including sciences. One factor contributing to the downturn is the prioritization of postgraduate programs and the resulting increase in the number of full professor posts, which in turn led to a decrease in the number of entry-level posts for young academics such as assistant professorship. In the case of law, the new law school system was the straw that broke the camel's back. Contrary to the original ideal of producing legal professionals who were versed both in theory and practice, the focus has shifted to the practice side, and very few - if any - law school graduates seek a career in research. With many universities favoring teachers with practical knowledge, research-focused teachers are also finding it increasingly difficult to be hired by other universities. No wonder students shun academia.

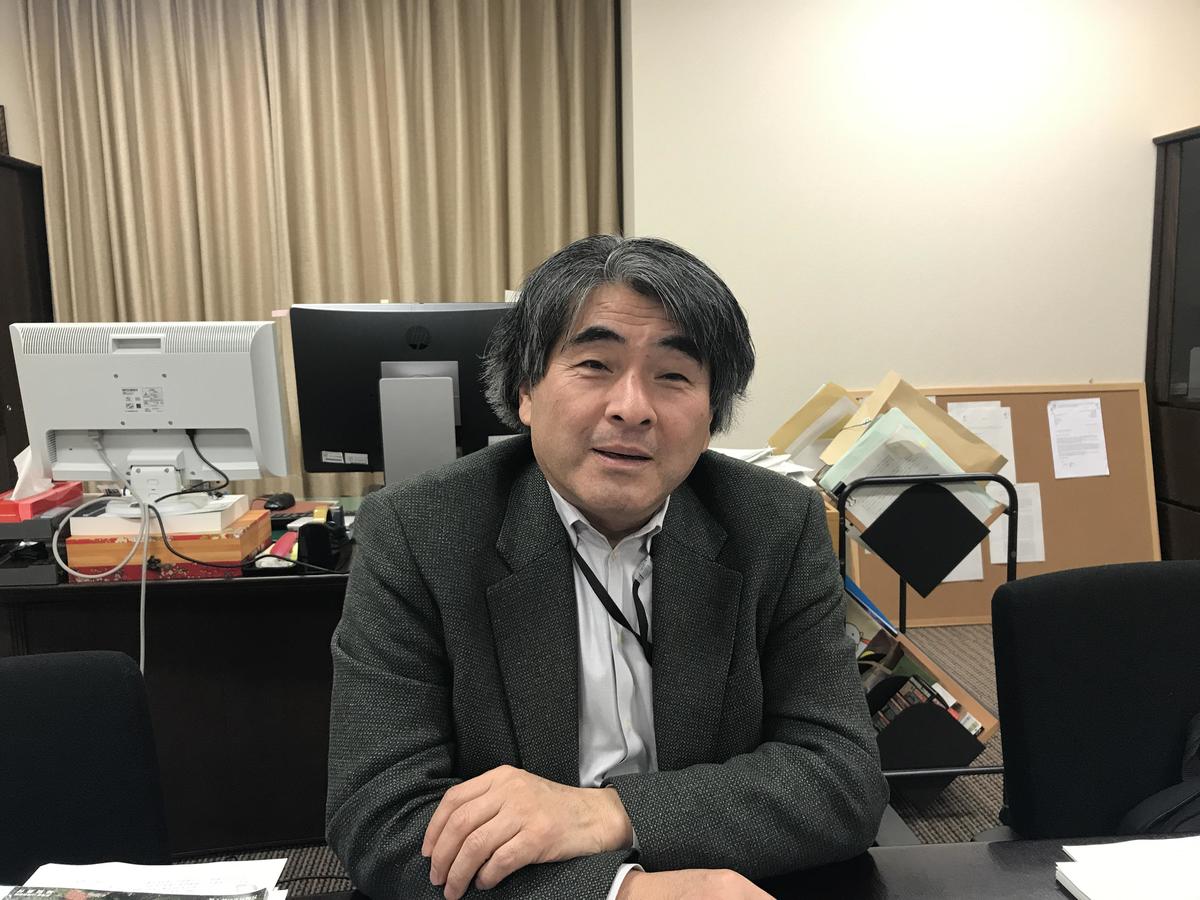

"When the law school system was introduced, we were concerned about the impact it might have on researcher training; I'm afraid we have been proved right," says Professor Hajime Wada, Vice President. Japan was once renowned for producing jurists with first-class research output and international recognition. These days, in his field of labor law, the number of researchers across Japan has gone down so dramatically that he knows the faces of most of them.

In these uncertain times, the role of law scholars is as important as ever. "Whether it's the population problem or employment issues, there is a need for specialists who can see the broader picture and guide system-level policymaking based on a clear vision," says Wada.

Professor Katsuya Ichihashi agrees: "in the realm of law, it is important that theory, institution and practice interact and influence one another to create a good system." The key is that the three elements of this trinity work flexibly to suit the given circumstance; an institution may emerge from practice and theory, or an institution may be established first and theory and practice may follow. The Constitution of Japan is a good example. It is founded on the principle of constitutionalism, which was a subject of theoretical study in the era of the pre-war Meiji Constitution. This theoretical foundation allowed a new institution to emerge and practice to be established when the new Constitution was adopted after the Second World War. On the other hand, Article 24 of the Constitution, which states that marriage shall be based only on the mutual consent of both sexes, came as a progressive new institution alien to the society where arranged marriages were common and parental consent was required by law. The arrival of this new institution transformed the society. In the case of a country like Vietnam, where Meidai is providing legislative assistance, theory and practice are yet to be established. As a result, the first step of the process is to establish a legal institution so that theory and practice can develop from it. The weakening of scholastic vigor at universities may weaken the theoretical robustness, and he is concerned that this may unbalance the trinity that supports law.

Another concern for him is that the current jurisprudence in Japan tends to take supreme court case law as gospel, so much so that the focus seems to be on making sure everything is consistent with it. Teachings at law schools are also governed by this preoccupation. This is like keeping fish in a pond instead of allowing them to swim in the wide ocean. Jurisprudence ought to be a pursuit of theory independent of practical law - even if that comes from the highest court of the land - and application of theory to practice. Lively new debates on aspects of legal theory are emerging across the world, for example, about how the legal institution should deal with the sometimes blurred line between public and private in the real world. The way law is researched in Japan, however, does not encourage endeavors to tackle such new challenges.

Professor Kaoru Obata, the Director of the Nagoya University Center for Asian Legal Exchange (CALE), the body that runs CJL, also stresses that lawyers must have the ability to look at the past, present and future and compare different countries around the world to form a vision of the most reasonable form of institution that would make sense to the affected parties. This ability cannot develop if students only learn the prevailing orthodoxy and case law based on the current body of laws. What students of Asia need to study - and, importantly, what law faculties across Japan should be teaching - is comparative Japanese law and its historical context, he says. CJL operates at eight institutions in seven Asian countries including Vietnam, and Obata is currently working to turn it into a consortium through which other Japanese universities can also be involved in the initiative. His ambition is to use it as a vehicle to stir up the stagnant waters of law education and research in Japan. The idea behind the way the law school system was implemented was to put out as many as possible and let the process of natural selection weed out the weak. Obata likens it to "numerous little boats fighting it out at the top of the Niagara Falls trying to push other boats over the edge." There is no future for law education or research in a place like that.

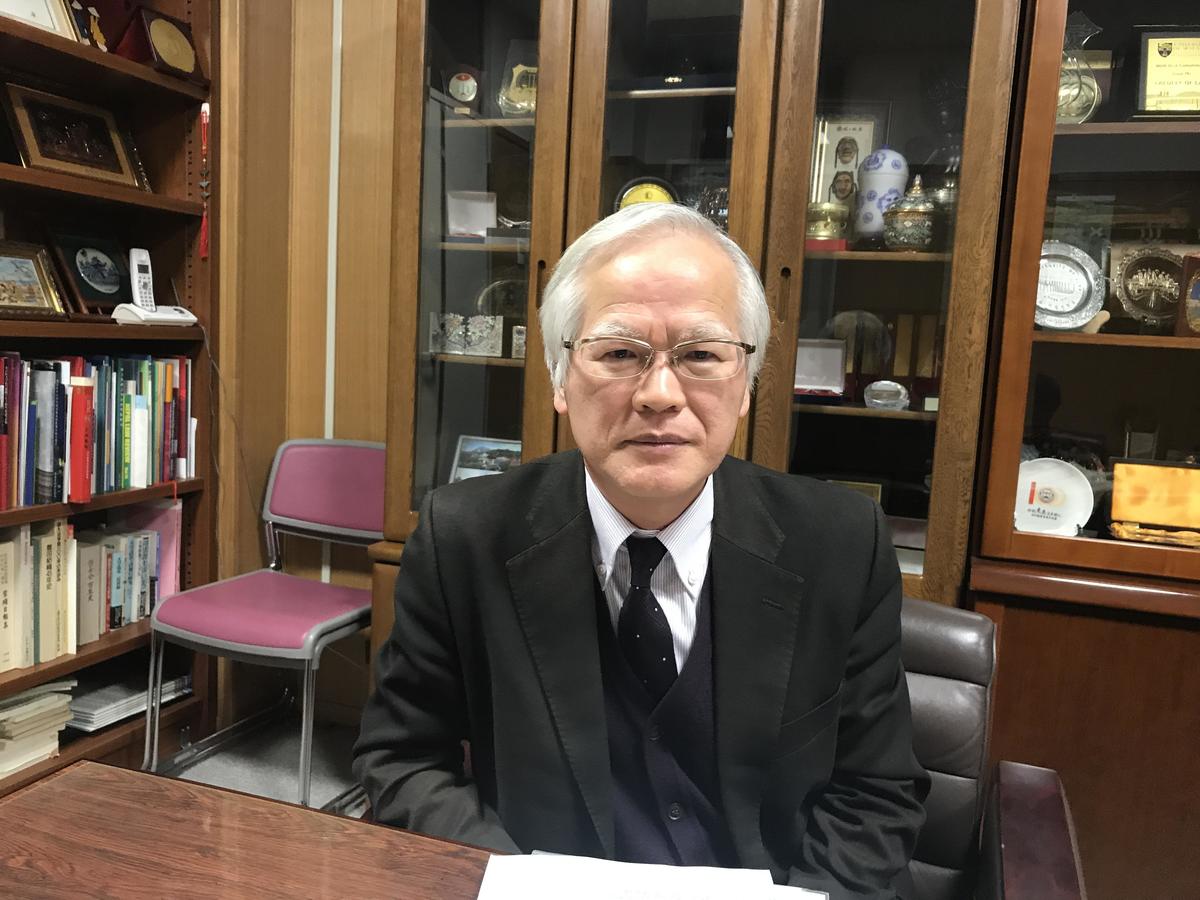

Mitsuki Ishii, Dean of the School of Law

Mitsuki Ishii, Dean of the School of Law

A symposium was held in Tokyo recently where experts from Japan and the US discussed artificial intelligence (AI). Masaru Kitsuregawa, Director General of the National Institute of Informatics, gave a keynote speech on the topic of information technology and law. The rapid advancement of AI is transforming the society. He stressed the importance of providing new legal institution and framework to meet this challenge. If handled wrong, law could hinder technological development or allow infringements of individual rights.

The same also applies to the matter of life. With the development of assisted reproductive medicine and use of genetic information picking up speed, the law is not keeping up with the pace of progress.

The Japanese Civil Code came into force in the patriarchal Meiji Era, and the United Nations has repeatedly urged Japan to amend some of the outdated provisions such as the period in which a woman is prohibited from remarrying, and the gender difference in the marriageable age. There is a pressing need for reform as we ask ourselves what sort of society we want to live in.

Now more than ever we need visionary law experts who can tackle the challenges of changing society, and it is ironic that training of law scholars is in crisis. Looking at other universities nationally, larger universities such as the University of Tokyo and Kyoto University seem to be able to maintain their scholarly incubation system, but many state universities are facing the same issue Meidai is experiencing. The situation is bleak. A tall mountain requires a wide skirt. In order to ensure diversity, what we need is not the tall and solitary Mount Fuji but the numerous peaks of Yatsugatake Mountains.

Another serious issue affecting Meidai is the headhunting of teachers by other universities, particularly private universities in the capital region. Many teaching members at Meidai are extremely busy, with the pressure to win external funding to pursue research in the face of continuing budget cuts, increasing teaching hours to cover both their own specialisms and law school subjects, and the requirement to provide legal expertise within the university. Being part of the Meidai faculty may have its advantages, but one cannot blame those who feel that a move to a private university, with more time for research and later retirement age, seem attractive.

It used to be that young researchers were inspired by the sight of their mentors immersed in their research, but these days those in the mentors' role are absolutely exhausted, says Dean Mitsuki Ishii. This alarming situation is what drove him to set up a special program titled Equip MIRAI last year, in a bid to increase the number of undergraduate students interested in continuing their study at the postgraduate level. It seeks to show how exciting research can be. "Mirai" means the future in Japanese, but the first two letters of the program's name also allude to the nature of its ambition: Mission Impossible. The response has been encouraging; they already have several students moving on to postgraduate courses. In the next step, he hopes to increase the number of assistant professor posts for students to take at the end of the courses.

The last 10 years or so since the establishment of the law school has been a lost decade, where very few new researchers entered academia, says Professor Wada. Perhaps the time has now come to review the provision of law research and education, including the law school program, and carry out a fundamental reform - to safeguard the future of the country.

Subscribe to RSS

Subscribe to RSS