February 5, 2019

What If There Was No Mass Graduate Recruitment

It is staggering, if you think about it, what an enormous impact the Japanese practice of annual recruitment has on university education. I have been thinking about this since I heard a talk by Professor Yoshiaki Kawajiri of Nagoya University's Graduate School of Engineering at a public symposium titled "Rethinking the employment and recruitment of postgraduate engineering students", held at the University of Tokyo in December 2018, on the topic of current employment and recruitment practices and their effect on postgraduate engineering education. The symposium was organized by the Eight-University Engineering Association, an alliance of the undergraduate and graduate schools of engineering at the seven former imperial universities and the Tokyo Institute of Technology. The Association is currently headed by Professor Norimi Mizutani, Dean of the Nagoya University Graduate School of Engineering. What prompted the Association to organize this event was an increasing sense of alarm at the way annual mass recruitment of graduates is disrupting masters-level education and research.

Kawajiri's talk, titled "the employment and career development of engineers in the US", was an introduction to engineering graduate recruitment in the US, where there is no annual mass recruitment. He also explained how long-term student internships were run through partnerships between universities and host companies. In the US, companies recruit throughout the year; the concept of an annual recruitment window when all companies hire new graduates en masse is alien to them. This means that students can graduate at any time of the year and can delay graduation if they wish to spend more time beefing up their resumes. The symposium was subtitled "in order to produce highly skilled engineers ", and Kawajiri is convinced that companies can help by recruiting graduates throughout the year, which he believes would expand the horizons of university education. Wanting to hear more, I visited him at his laboratory.

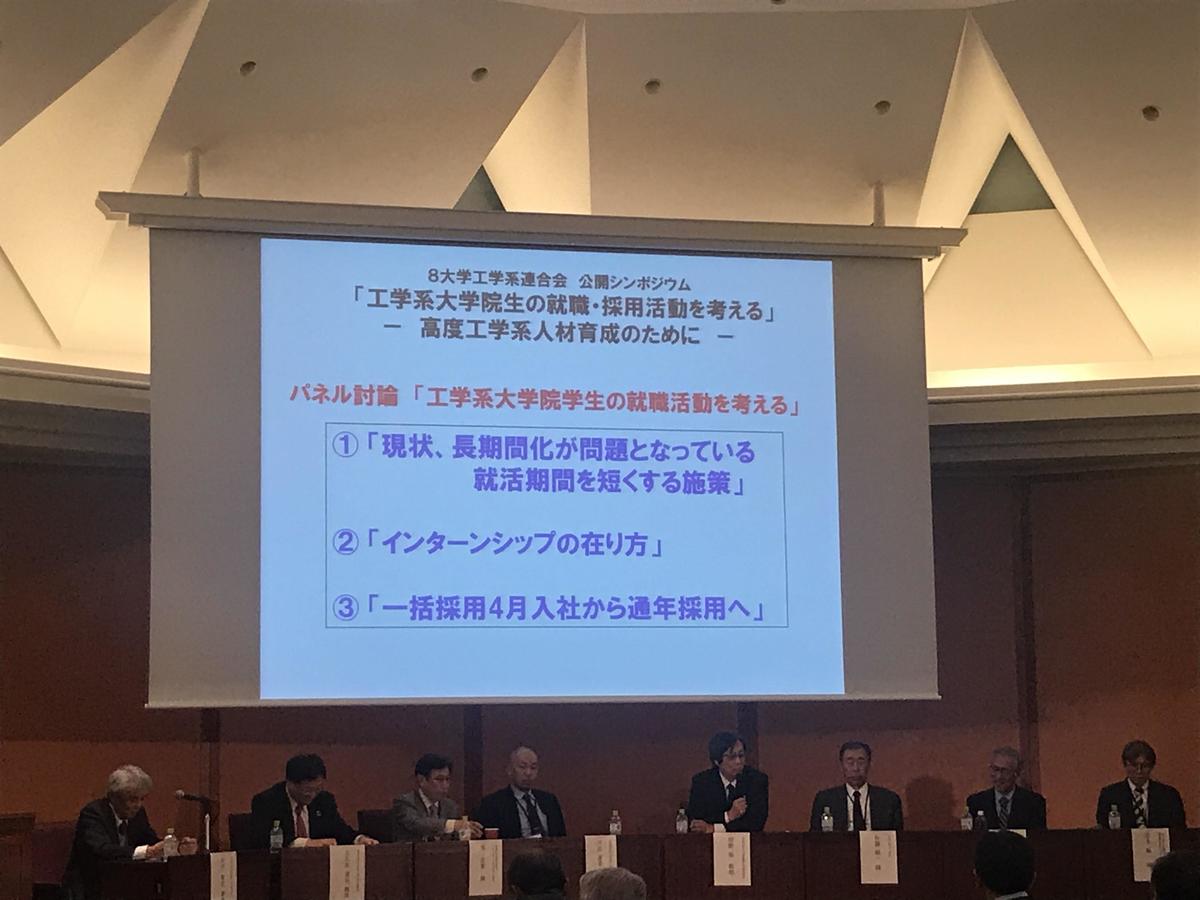

"Rethinking the employment and recruitment of postgraduate engineering students" symposium. Industry representatives joined academics for a panel discussion (December 18, 2018, the University of Tokyo)

"Rethinking the employment and recruitment of postgraduate engineering students" symposium. Industry representatives joined academics for a panel discussion (December 18, 2018, the University of Tokyo)

Kawajiri certainly knows what he is talking about; he had been employed by a Japanese company before he went to a US university to gain his doctorate. After a year in Germany as a post-doctoral fellow, he taught at the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech), initially as an assistant professor then later as an associate professor. He returned to Japan in June 2017, after 14 years abroad, to take up a professorship at Nagoya University.

His talk on the differences between the graduate job markets in Japan and the US was based on his own experience. In the United States, engineering students commonly enter the job market either straight after finishing undergraduate study or after completing a 5-year doctoral program. This is in stark contrast to Japan, where most students seek employment after completing a master's course. It is often lamented in Japan that too few students continue their study to the doctoral level, and pay is clearly a significant factor here. A study by the Department of Chemical Engineering at the University of Illinois reports that bachelor's degree holders in the US earn around $69,000 p.a. on average, whereas the average for doctorate holders is around $114,000 p.a. - more than 1.6 times higher. In Japan, the difference tends to be much smaller; one manufacturer, for example, pays bachelors degree holders 220,000 yen, masters 240,000 yen and doctors 290,000 yen in the first year of employment. The monetary benefit one can gain from a doctorate is so small that it is hardly worth paying extra three years' tuition fees for a doctoral course.

When recruiting degree holders, American companies look for highly specialized knowledge and specific skill sets. A graduate job seeker would send their resume to companies that match. The selection process that follows, in Kawajiri's experience, typically goes like this: in the evening before the interview, go to the town where the company is located, to be picked up at the airport. Have dinner with the company's representative and stay overnight at a hotel. Go to the company's office in the morning for interviews, with staff members of the department to which you will be assigned if you get the job, as well as your potential future boss. There is also a research seminar. The process takes all day. The focus of the interviews is your research, and questions are detailed - what was it about? How does it relate to the company's research field? The pay and benefit package is only indicated if you are accepted. The package can be negotiated at this stage. When that is done, you sign a form confirming your acceptance of the terms of employment and - congratulations! - you are hired.

There is no Japanese-style entry sheet, and no pre-specified pay and benefit conditions indicated at the beginning of the recruitment process. Recruitment process is all about assessing the ability of the student, and the student gets a salary that matches their ability. Companies in the US recruit graduates to fill specific jobs, unlike in Japan where employment means joining the membership of a company.

Professor Yoshiaki Kawajiri of Graduate School of Engineering, who specializes in process systems engineering.

Professor Yoshiaki Kawajiri of Graduate School of Engineering, who specializes in process systems engineering.

It is only natural that, when it is your ability that matters, you try your best to maximize it. And that's where internship comes in, as Kawajiri explained in his talk. The American concept of internship is world apart from the short-term - some as short as just one day - internships that are causing concerns in the Japanese job market. Although some Japanese universities do offer relatively long-term internships, the US program, also known as cooperative education or co-op for short, goes much further. The student intern would spend a whole semester (four months), full-time, with a company approved by their university, and repeat this 3-4 times over the course of their study until graduation. It is a well established practice with nearly a century of history.

At the Georgia Tech School of Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering where he taught, around 35% of students took part in co-op, and those who did tended to perform better on the course. This also chimes with his own experience; studying can be a chore when you have no idea whether your research has any point. Work experience can give you a valuable insight into what your research might mean to the wider world, which in turn motivates you to do better. Taking time out of study to intern may mean taking longer to graduate, but it is no detriment to your employment prospect in a job market where companies recruit throughout the year.

The introduction of year-round recruitment in Japan would make corporate internship a much more feasible option to consider. It would also make it easier for students to study abroad. Japanese students are often accused of being inward-looking for not going abroad, but it is more of a pragmatic decision faced with the reality of annual mass graduate recruitment. If you do not need to graduate at the same time as everyone else, then going abroad would not be such a huge, difficult decision. It would also make it easier for students to choose double major, for example adding artificial intelligence or computer studies to their main major. These options can all broaden students' future potential.

Back when Japan was enjoying a rapid economic growth, universities needed simply to churn out largely homogeneous batches of graduates each year. Today, businesses need mavericks with original and unique ideas. With Japan's once famed scientific and technological prowess on the wane, what can universities do to produce the next generation of talents that shape the future? "We have no time to waste," says Kawajiri. As part of the government-led Doctoral Program for World-leading Innovative & Smart Education (WISE), Meidai is starting a new graduate school program called the DII (Deployer-Innovator-Investigator) Collaborative Graduate Program for Accelerating Innovation in Future Electronics. The program aims to produce doctorate holders who can turn research outcomes rapidly into practical applications and is planned to include a half-year overseas internship. Kawajiri hopes that the program will present a new model for future engineering education.

"The problems universities and companies are facing are interlinked," said Professor Tatsuya Okubo, Dean of the School of Engineering at the University of Tokyo, at the symposium. And these problems are huge. Universities are seeing the quality of research papers drop, and this is negatively impacting the overall level of science and technology in Japan. Companies are falling behind the global trend and no longer have the capacity to train engineers or conduct research in-house. This means they increasingly look to universities for both education and research, but a survey conducted the graduate schools of engineering across the Eight Universities show that 70% of master's students due to graduate this spring have had to spend over four months job-hunting. As students devote more time to the job market, university education and research suffer. This is a catch-22 situation.

Recruiting new graduates en masse once a year may be efficient, but, as Kawajiri says, it puts a constraint on what universities can do. Nevertheless, half of the students who took part in the survey said they supported the practice, so it seems plenty of students like it the way it is, while only one in ten students were against it. Critical comments included: "job hunting was a considerable burden on what could have been the best time to do research"; "we are basically told that we have only one chance of success when we graduate - you miss it and that's game over for the rest of your life"; and "it's inconvenient that there's no recruitment outside a narrow window."

The mass recruitment practice is deeply embedded in the way the Japanese society operates, and decoupling it would not be easy. That does not mean, however, that we should not try. What if students could graduate later without being disadvantaged in the job market, for example? We can make these changes little by little to make the talk of being "game over" a thing of the past.

Professor Hiroaki Suga of the University of Tokyo made a practical suggestion at the symposium, which was later published in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper as a point-of-view column. The main thrust of the proposal was to limit the mass recruitment period to three months immediately before the end of the academic year for STEM postgraduate students. This would allow them to focus on their research until the end of December and hone their research skills. Companies would benefit too as they would be able to recruit new graduates based on their masters dissertations. Universities would also reap rewards given the enormous contribution master's students make to universities' research output.

Suga's proposal has caught the eye of Professor Hisashi Yamamoto, University Professor at Meidai. Formerly of Nagoya and Chicago Universities and now a professor at Chubu University, Yamamoto is also a former president of the Chemical Society of Japan. He has been vocal about the future of universities and research endeavors in Japan, making various suggestions and recommendations himself. While it is essential that a fundamental debate takes place about how to tackle Japan's decline in science and technology, Yamamoto believes that it is also important to make changes where possible now. He insists that STEM disciplines need to be looked at separately from arts and social sciences, especially when it comes to postgraduate education. As regards the issue of recruitment, what concerns him is the loss of trust between corporate HR departments and university faculty members. Part of the problem, he suspects, may be that universities are not doing the kind of research that meets the expectations of the wider society. Perhaps academics must also need to have a hard look at themselves.

I met up with a student for a chat. He is due to graduate from a master's program at Meidai's Graduate School of Engineering and start working at a manufacturing company this spring. He had thought about a doctoral degree when he started at Meidai but was put off by all the talk of hardship and suffering he heard from students on doctoral courses. In the end, he felt it was too much to ask his parents to take the financial burden of extra years and decided to get a job instead. He still finds the idea of a career in research attractive, however, and would like to think about the next step after starting the job. He has done some short-term internship programs since the first-year summer holidays and regrets that the recruitment season kicked off just at the time when he felt he was getting going on the master's course. He had to devote so much of this time job hunting that, in March and April, he had to abandon his research altogether. He was only able to restart again after he received the news of conditional acceptance in June from the company he targeted. He has worked hard to make up the lost hours since then. "Getting the job was a big relief," he laughs, "I felt secure enough to be able to focus on my research again."

Looking back on the experience of job hunting, he feels it was positive; visiting and talking to many companies during that period opened his eyes to the wider horizons. He would have liked to study aboard if he could, but delaying graduation by a year was not a feasible option for him.

"I'd like to be at the heart of manufacturing," he enthuses. Universities must think what they can do to help young people like him gain the necessary knowledge and skills to fulfill their potential. As the industrial structure of the country goes through a fundamental change, how can Meidai's School of Engineering educate the next generation of leaders? Huge expectations, and responsibility, are on their shoulders.

Subscribe to RSS

Subscribe to RSS