December 6, 2019

Inspiration from Myanmar to Think Back Upon Our Predecessors

At the end of October, Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine Professor Nobuyuki Hamajima visited a village hospital in Gyobingauk Township, about four hours by car from Yangon, the former capital of Myanmar. The local hospital is a small private facility with 50 beds, yet there was a reason he had paid a visit from so far. It was established in 2013 by a Meidai Graduate School of Medicine alumnus who studied healthcare administration and is now aiming to create a new model for regional healthcare. Hamajima was visiting to observe how things were progressing and see what kind of assistance he could provide.

In Meidai’s effort to foster talent throughout Asia, the healthcare is one of the most important fields as it has direct connection to human life. Those who have studied at Meidai have gone on to flourish in various roles, working to improve the medical systems in their home countries. Hamajima provides guidance as an expert in healthcare administration, and wants to keep close contact with graduates in order to offer necessary support. The state of healthcare varies greatly from place-to-place, however, and it is impossible to provide effective support withoutgiving this due consideration. He therefore makes use of various opportunities to visit the places where graduates work. On this occasion, another goal of his trip was a meeting regarding a cooperative agreement between Meidai and University of Public Health, Myanmar’s only school for public health, to be concluded at the beginning of next year.

The hall of Aung Myin Myint Mo Hospital. On either side are examination and testing rooms, a pharmacy, and other offices. The chairs can be removed and the space also used for events.

The hall of Aung Myin Myint Mo Hospital. On either side are examination and testing rooms, a pharmacy, and other offices. The chairs can be removed and the space also used for events.

The hospital was founded by Dr. Nyi Nyi Latt, who was an official at Myanmar’s Ministry of Health and Sports (formerly the Ministry of Health). In 2005 he was selected from over 1,000 applicants in Myanmar to become the first from the country to join Meidai’s healthcare administration master’s course, established as part of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology’s (MEXT) Young Leaders Program (YLP) scholarship system. He studied in Japan for one year researching trends in cancer patients, and after getting his master’s degree he returned to work. Then in 2014 he participated in the Transnational Doctoral Programs for Leading Professionals in Asian Countries at Meidai’s Asian Satellite Campuses Institute, this time getting his doctorate over four years while working on the topic of tobacco control.

Both of these programs endeavor to develop future leaders across Asia in government and other fields. As Nyi Nyi Latt had become the lead-off batter from Myanmar, he was expected a lot to transform the country’s healthcare policy, yet he felt the limits of working for a government under the influence of a military regime. After mulling it over for a time, he decided to quit the job and return to his home region to build a hospital.

Dr. Nyi Nyi Latt standing at the hospital reception. Dressed in a lungi, the traditional garment of Myanmar, he tirelessly patrols the hospital and speaks with colleagues. He is truly full of energy.

Dr. Nyi Nyi Latt standing at the hospital reception. Dressed in a lungi, the traditional garment of Myanmar, he tirelessly patrols the hospital and speaks with colleagues. He is truly full of energy.

In the healthcare system of Myanmar, state-run hospitals basically provide medical treatment for free, and patients pay only for medicine. In Nyi Nyi Latt’s region, however, the public hospital has only three full-time physicians, and it cannot provide specialized healthcare. With the support of his relatives, he established Aung Myin Myint Mo Hospital and outfitted it with facilities and arrangements to provide specialized medical treatment. It has departments for internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, orthopedic surgery, psychiatry, otolaryngology, dermatology, radiology and other specialties, and employs a total of over 200 staff, including 10 full-time and 12 part-time doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and office staff. He has also installed modern equipment, like the latest type of X-ray machine that exposes patients to minimal radiation. When more advanced treatment is necessary, patients are sent to a hospital in Yangon.

The burden on patients for medical expenses isn’t small, yet they visit in large numbers to be examined by specialists. Treatment is sometimes provided for free to those who absolutely cannot afford it.

Nyi Nyi Latt recognizes that it isn’t an easy task for a non-for-profit hospital like this one to operate without support from the government. While securing revenue in various ways, such as through test fees, he strives to create an environment where staff can always feel strong motivation towards their work, and asks that they “treat patients as if they are your own parents.” One part of creating this environment is a general meeting attended by supervisors from all departments, where, in addition to status reports, they proactively exchange opinions and ideas about issues.

Over two days, Hamajima observed the hospital facilities and wards. “I was impressed to see the outstanding effort given as they work cleverly within existing limitations,” he said, and expressed hope that this will become a new model for advanced healthcare in Myanmar.

Professor Nobuyuki Hamajima (right) explains to nurses how to use the medical equipment he brought, such as devices for measuring blood pressure and blood sugar.

Professor Nobuyuki Hamajima (right) explains to nurses how to use the medical equipment he brought, such as devices for measuring blood pressure and blood sugar.

“Studying abroad at Meidai not only provided me with knowledge, but also the opportunity to meet new colleagues from other countries. This helped me greatly expand my previously narrow outlook,” explained Nyi Nyi Latt. In particular, studying and spending time together over one year on YLP has given the 10 students from throughout Asia a strong connection.

YLP was founded by MEXT with the goal of fostering leaders within Asia. The program offers four courses at three other universities besides Meidai, including the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies. These other courses are in the fields of public administration and business, and Meidai is the only school to offer a healthcare program. Former School of Medicine Professor Katsuki Ito (currently an executive advisor to Meidai) had a hand in the 2003 start of the program, and believed that economics would also be essential when students returned to their home countries and dealt with healthcare policy. After much deliberation within the school, it was decided that a healthcare administration course would be offered. Ito reflects back that, in organizing the course “We ourselves ended up learning the most,” as the field was actually understaffed in Japan at the time and it was the first time for Meidai to embark on the field.

The program is aimed at residents of 13 countries throughout Asia, and students are primarily selected from doctors and other professionals connected to each country’s ministry of health. While attending lectures and visiting facilities, each student writes a thesis using data they collected beforehand on healthcare in their own country. “We want students’ experience in Japan to be useful when they think about policy in their own country,” explains Associate Professor Eiko Yamamoto, who took charge of YLP while focusing on Asia as an obstetrician and gynecologist.

As of September 2019 there have been 182 graduates, many of whom have gone on to become directors or chiefs in the ministry of health of their own country. Seventeen students have come from Myanmar, one of the most well represented nations after countries like Mongolia and Cambodia. At the YLP 15th anniversary ceremony held last year, Nyi Nyi Latt gave a speech on behalf of all graduates.

Seeing these graduates reminded me of Shinpei Goto, who was president of Aichi Medical School, the predecessor of Meidai. A mini exhibition called “Shinpei Goto — The Nagoya Years” that details his time as a young doctor was on display till the end of November at the University Medical Library. During the exhibition, a special lecture was also given by Professor Emeritus Atsuko Aoyama titled “Public Health — Protecting the Health of the People: From the public health established by Shinpei Goto to global health.” Goto also served as the mayor of Tokyo, and is credited for having built the backbone of the modern city of Tokyo through reconstruction in the aftermath of the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake. But in Nagoya he poured his heart into health — protecting the health of the people. This public health movement lead to what we today call global health. At the same time, this was the starting point of his career as an administrative official and politician that championed “protecting the life and health of the people” and has been praised throughout the years.

Making contributions to protecting the health of people in developing nations could be considered as continuing the legacy of Goto, who did the same so far in the past.

“Illustration of a surgical operation taking place at Aichi Prefectural Public Hospital in the early Meiji period.” Shinpei Goto (center) kneeling down to operate (University Medical Library archives)

“Illustration of a surgical operation taking place at Aichi Prefectural Public Hospital in the early Meiji period.” Shinpei Goto (center) kneeling down to operate (University Medical Library archives)

Goto was born in 1857 in the current city of Oshu, Iwate Prefecture as the son of a samurai in the Mizusawa Clan. The clan clashed with the new Meiji government, so Goto worked his way through medical school. His patron became the governor of Aichi Prefecture, which helped him secure a position as doctor at Aichi Prefectural Public Hospital in 1876. The hospital had its own medical school, where Austrian physician Albrecht von Roretz had been hired by the Meiji government to work as a teacher. Roretz recognized Goto’s ability, and when the facilities were renamed to Aichi Medical School and Aichi Hospital in 1881, he was appointed head of both. Goto was just 24 years old.

The next year in 1882, when Liberal Party member Taisuke Itagaki was attacked while campaigning in Gifu, many physicians were hesitant to help out of fear of government retaliation, yet Goto rushed to provide him medical treatment. It is said that Itagaki commented ” It’s regrettable if he remains a doctor and not becomes a politician. “

An ukyo-e artist created an illustration of Goto during this time called “Illustration of a surgical operation taking place at Aichi Prefectural Public Hospital in the early Meiji period,” which is kept in the University Medical Library (see photo above). Goto is the doctor performing surgery in the center, while Roretz on the far left is administering anesthesia. The latter is drawn to look like an old man, but he was actually a young doctor at little more than 30 years old. Flanking Goto and supporting the patient’s arm is Ryokai Shiba, a skilled linguist from Sado Island who knew many languages and took up a position at the public hospital with Roretz. Shiba studied medicine under Johannes Lydius Catherinus Pompe van Meerdervoort, and created the Japanese translation of many medical terms, such as protein, duodenum, and nitrogen. He also appears in Kocho no Yume, a novel written by Ryotaro Shiba about doctors at the end of the Edo period.

A temporary public hospital and medical school, which later became the prefectural hospital and medical school, were established in 1871 by the Nagoya Clan. These institutions are said to be the very starting point of Meidai, and this treasured illustration preserved at the library conveys to us that beginning — also the dawn of modern medicine — as prodigies gathered together from near and far.

Two years after becoming director of the hospital, Goto left for the Sanitary Affairs Bureau at the Home Ministry, and from there became engaged in a variety of different activities.

On the public health side, he wrote the Principles of National Health, began chlorinated disinfection of the water supply, and promoted bathing in the ocean for health. During his time as civilian governor of Taiwan, he called for governance based on the principles of biology. He also pushed for improvement of basic public services like water, sewerage, and transportation infrastructure like roads, contributing to modern town development. He held a surprisingly diverse series of important roles, including first director of the South Manchuria Railway, Minister of Communications, first head of the Railway Bureau, Home Minister, Foreign Minister, and director of the Imperial Capital Reconstruction Bureau. He had the idea of introducing full-gauge railroad tracks, and even changed the color of mailboxes from black to red. In his later years he strove to bring morality to politics.

Hidehiro Gamo was in charge of managing documents related to Goto in the University Medical Library, and says, “Based on the ideas of public health administration and thinking rooted in scientific proof that he learned from the Vienna University-taught Roretz, he forged a new era with his strong will and great vision. We can only admire Goto’s way of living.”

Looking further back into history, there is one more prominent person who had a hand in the foundation of Meidai. This is Keisuke Ito, who was born in 1803 at the end of the Edo period in Owari Province (present-day Nagoya City) to a family of physicians. He learned Western medicine, then studied Western systematic botany under Philipp Franz von Siebold, and became a botanist known for coining the Japanese terms for things like stamen, pistil, and pollen. He was also the first Japanese person to obtain a Doctorate of Science. Along with establishing a vaccination institute and working to make vaccinations more widespread, he proposed the creation of a school of Western medicine to the Nagoya Clan with his medical colleagues. In 1871, this vaccination institute then became the aforementioned temporary hospital and school. Ito himself had moved to Tokyo the year before at the age of 67, and wasn’t directly involved. As the University of Tokyo and many other schools assume that their beginnings were in vaccination institutes, some say that 1852, when the institute was founded, is the very origin of Meidai.

At the age of 79, Ito became a professor at the University of Tokyo — founded just four years prior — and at the age of 86 got his degree.

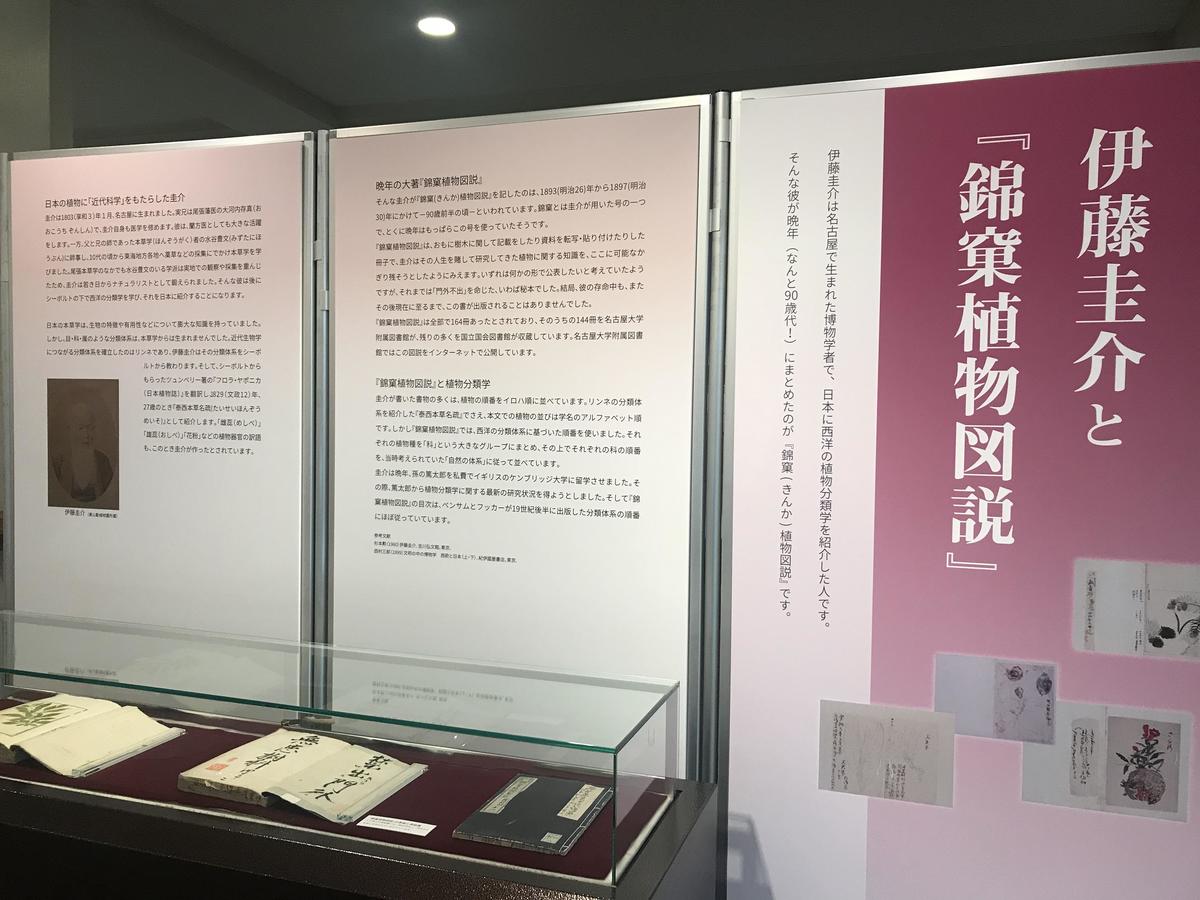

Kinka Shokubutsu Zusetsu, displayed at the “Botanical Art and an introduction to Plant Taxonomy” exhibition at the Nagoya University Museum. Ito clearly stated, “Do not remove from premises.”

Kinka Shokubutsu Zusetsu, displayed at the “Botanical Art and an introduction to Plant Taxonomy” exhibition at the Nagoya University Museum. Ito clearly stated, “Do not remove from premises.”

Ito’s Kinka Shokubutsu Zusetsu, a manuscript he hand-wrote when he was over 90 years old, is also featured at the “Botanical Art and an introduction to Plant Taxonomy” exhibition, running at the Nagoya University Museum until February 22, 2020.

For the exhibition, Professor Tetsuya Higashiyama of the Nagoya University Institute of Transformative Bio-molecules gave a lecture titled “Looking at Keisuke Ito’s world of flowers from the viewpoint of latest research” on December 11. Higashiyama is a botanist known for discovering the mechanism that guides pollen tubes, and researches those exact same themes — pollen, stamen and pistil — that Ito had termed. He was told about his great predecessor Keisuke Ito when transferring to Meidai from the University of Tokyo, but upon doing some survey on him, Higashiyama was surprised to find how capable scientists were at the end of the Edo period and what an Ubermensch-like figure Ito was. Ito had only studied under Siebold in Nagasaki for half a year, but the German scientist gifted him a copy of Flora Japonica written by Carl Peter Thunberg, a disciple of Carl Linnaeus, who is considered the father of Japanese botany. This goes to show how much trust Siebold had in him. And then, although there were not many reference books at this time, in one and a half years he translated it into Japanese and published it as Taisei Honzo Meiso.

It was then in 1896 when the spermatozoids of the ginkgo plant were discovered at Koishikawa Botanical Garden of the University of Tokyo, which has a link to both of them. It was a world-shattering discovery that helped soon push Japanese botany to the global forefront.

Former curator Masami Nozaki, who in the past oversaw an exhibition about Ito at the Nagoya University Museum, explained, “Combining herbalism, which had come into its prime during the Edo period, with Western botany greatly aided the development of Japanese botany.” Ito taught his grandson Tokutaro, sensing he would become his successor, and the youth went on to study at University of Cambridge and became the first Japanese person to give plants scientific names. In the 30th anniversary edition of the science journal Nature, published in 1899, Tokutaro Ito was also selected alongside Kumagusu Minakata as a special contributor from Asia. He thus became a world-renowned botanist.

As if Keisuke Ito could finally rest after seeing his grandson’s success, at the turn of the 20th century in January 1901, he passed away at 97 years old.

Nagoya Imperial University was established in 1939 with the hospital and medical school at its core. Nagoya University was then re-established under the new system in 1949. This year, 2019, is a celebratory year marking 80 and 70 years respectively since their establishment. In 2021 it will be 150 years since the founding of the temporary hospital and medical school that preceded the university. We should take this opportunity to think back upon the wills and aspirations of our predecessors. I would very much like their legacies to be passed on to future generations.

Subscribe to RSS

Subscribe to RSS