January 31, 2020

Land Design with a Vision for 100 Years in the Future

While 2019 marked 60 years since the Typhoon Vera, or the Isewan (Ise Bay) Typhoon, it was also a year in which Japan received a repeated battering from large-scale typhoons Faxai (Number 15) and Hagibis (Number 19). Then soon after the start of 2020, January 17 was the 25th anniversary of the Great Hanshin Earthquake. As a year that signals a milestone, newspapers, TV programs and other media produced various special content on the event. One week later, the Japanese government's Headquarters for Earthquake Research Promotion announced evaluation results that indicate there is a probability of 26% or more that an earthquake along the Nankai Trough could cause a tsunami of three meters or higher, which would hit somewhere between the Izu area of Shizuoka prefecture and east Kyushu. The possibility of a powerful typhoon like a "Super Typhoon Vera" was also pointed out, all of which inevitably made us feel at the start of the new year that we are again facing the risk of a major disaster. It is no wonder why some argue that people shouldn't live in dangerous areas, and that we need to rethink our land use.

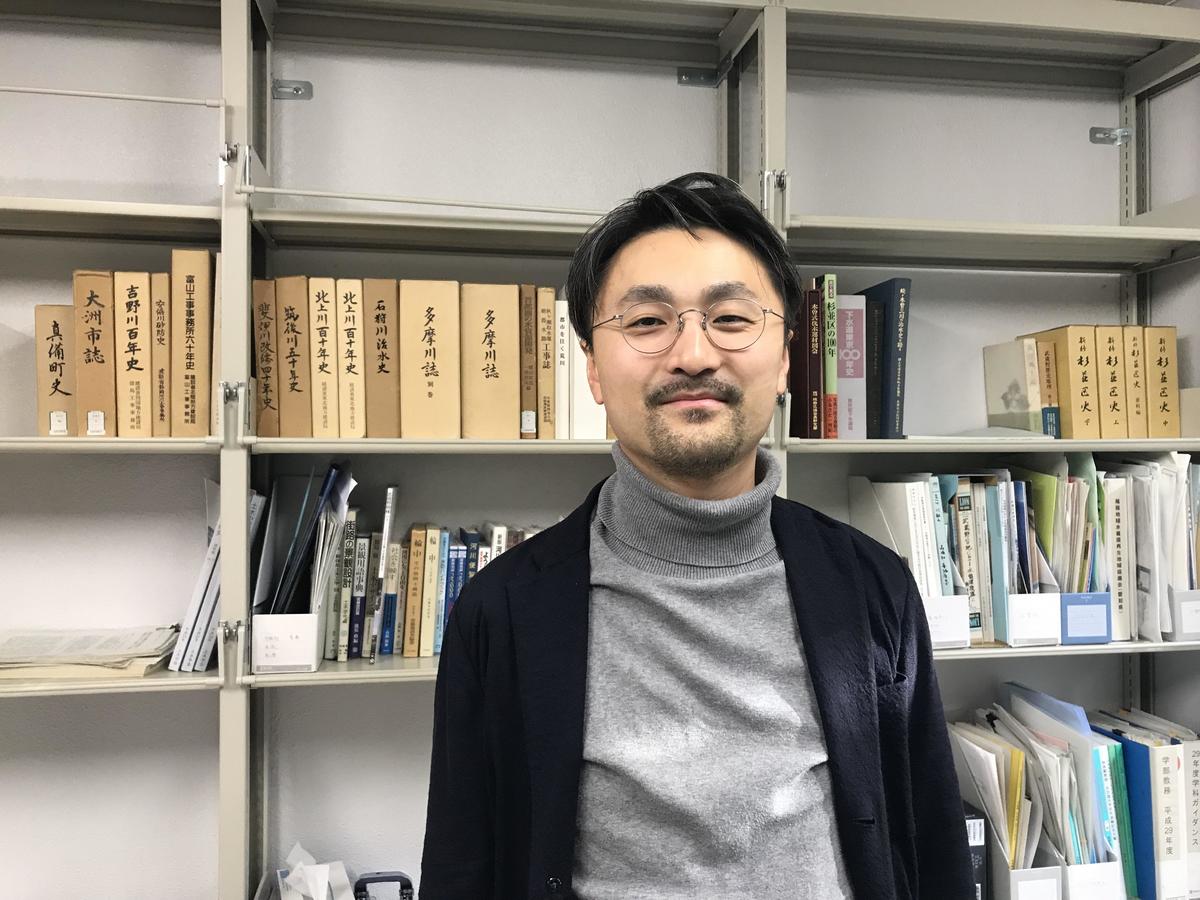

Founded in the wake of the Isewan Typhoon, Nagoya University School of Engineering's Civil and Environmental Engineering program has launched a new subject to engage in this challenge: land design. Design in this sense is not the simple act of designing, but encompasses a wider meaning of both planning and design. It traverses the boundaries inside civil engineering, and involves surrounding fields as well, to consider policies for land use that make it possible to live safely and comfortably. Associate Professor Shinichiro Nakamura of the Graduate School of Engineering transferred from the University of Tokyo after being selected from respondents to a public job advertisement when the Land and Infrastructure Design Lab. was established in 2014, and he is enthusiastic about "engaging in discussions on the theme with a vision for the country in 100 years." It is a field anticipated to contribute greatly to by utilizing all the knowledge and experience available as the university in Nagoya -- a city that has in the past been struck by a major disaster, and where preparations for future major disasters is a key issue.

Associate Professor Shinichiro Nakamura

Associate Professor Shinichiro Nakamura

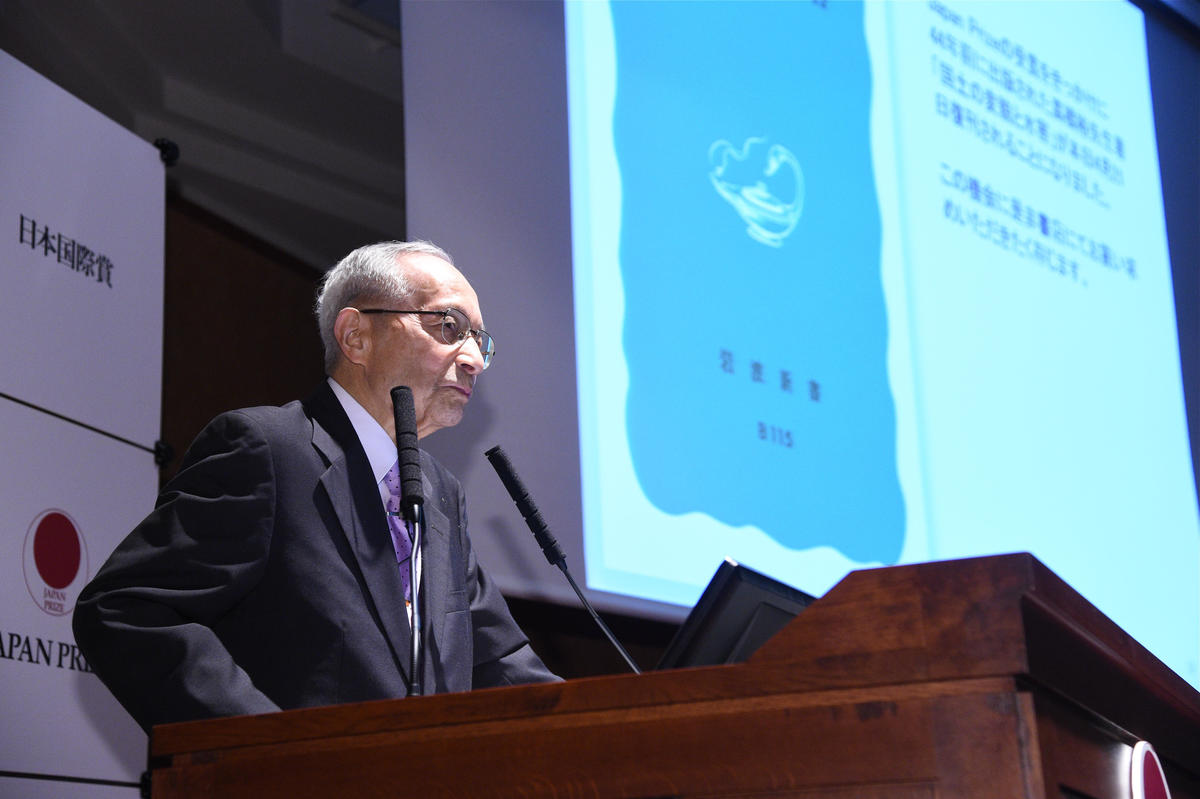

As a mentor, Nakamura looks up to internationally-renowned river engineer and Professor Emeritus Yutaka Takahashi of the University of Tokyo. In 2015, Takahashi became the first person from the civil engineering field to win the Japan Prize, which recognized his contribution to development of innovative concepts on river basin management and reduction of water-related disasters. Rather than relying only on structures like riverbanks, he strove to combat flooding through river basin management with techniques such as employing regulation ponds to collect rainwater, and changing land use. He is the father of these ideas that are now mainstream, and the Japan Prize awarded his "creation of the universal concept of river basin flood control that is useful globally, and contributions to water-related disaster risk reduction around the globe."

At a special symposium on the Isewan Typhoon held at Meidai's Disaster Mitigation Research Center in November 2019, Nakamura pointed out that the urbanization of rapidly-developed Nagoya is a factor behind the Isewan Typhoon while introducing Takahashi's remarks that the Isewan typhoon was "the land's tangible reaction to reckless rapid growth." This is a quote from Takahashi's 1971 book Kokudo no Henbo to Suigai (Transfiguration of Home Land and Flood) that sets forth the idea of river basin flood control, which was reissued after he won the Japan Prize.

Behind these remarks is Takahashi's river science, which is thinking about both natural and societal history of how a country's land has come about, and looking at society through rivers. In Takahashi's 2012 book Kawa to Kokudo no Kiki -- Suigai to Shakai (Crisis of Home Land and River -- Floods and Society) he went further to say that, "On the alluvial plane where the modernization and post-war economic development of Japan took place, the potential for disaster is insidiously increasing to the extreme." Seeing the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami as the harbinger of an era of great disasters, he writes, "We need to pool together wisdom -- including philosophy and other cultural wisdom -- to make Japan into an even safer and better place to live."

Nakamura is young enough to be the grandson of Takahashi's disciples, and has taken it upon himself to be a successor of Takahashi's river science. "It's certain that, up till now, our country's land has been used by unreasonably pushing the limits," he says, "and it is indeed now necessary -- in the face of a declining population, and predictions of intensified climate change-induced disasters and sea levels rises -- to consider ideas of land use with a long-term vision focusing on river basins, so that nature and humans can live in harmony." He says he wants to put these ideas to work in regional communities and bring any challenges that emerge back to academia to consider what research is necessary, then return those achievements to society. He is also running programs at local elementary schools where, through activities like riverside cleanup, children think about why trash ended up there, where it came from, and link those realizations with larger issues.

Professor Takashi Tomita of the Graduate School of Environmental Studies joined the Land and Infrastructure Design Lab. in 2016. He specializes in costal engineering, and researched tsunami and flood tides at the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism's Port and Airport Research Institute before returning to his alma mater. For a country like Japan, which depends on imports of things like energy and food, maintaining functioning harbor infrastructure is an extremely important issue. It's the reason why the words "Infrastructure Design" is included in the lab's name. Tomita says that, focusing on this, he wants to strive towards building a nation with disaster risk reduction at its core.

Professor Emeritus Yutaka Takahashi, the University of Tokyo, giving a speech at the 2015 Japan Prize awards ceremony (photo provided by the Japan Prize Foundation)

Professor Emeritus Yutaka Takahashi, the University of Tokyo, giving a speech at the 2015 Japan Prize awards ceremony (photo provided by the Japan Prize Foundation)

Professor Yoshitsugu Hayashi of the Graduate School of Environmental Studies is a specialist in civil works planning and transportation engineering who advocated for the creation of land design studies at Meidai. He is known for his international activities, and in 2015 was selected to be a full member of the think tank Club of Rome, which gained recognition after their 1972 report "The Limits to Growth" drawing attention to the crisis of humanity. He proposed a form of land design where various specialist fields work side-by-side to think comprehensively, as it is necessary for structural and non-structural measures to be unified in building a city for the future. Up till now there has been urban design and urban planning, but this would more widely design the country's land as a whole. When it comes to creating a sustainable society in the face of a demographic crisis, he believes the only way forward is "smart shrinking."

Since Hayashi moved to Chubu University at retirement, Professor Hirokazu Kato of the Graduate School of Environmental Studies has been driving the research. It is forecast that, by 2050, Japan's population will decrease to an estimated 95.15 million, just 25% of the population's 2004 peak of 127.84 million. It is estimated that the percentage of elderly citizens will have risen from 20% in 2005 to 40% in 2050. There is also a need to curb carbon dioxide emissions that are causing temperatures to rise, and reduce our environmental footprint. It certainly can't be said that the current situation is sustainable, with its sprawling metropolises and rapidly waning populations in decentralizing local regions. This is why making cities more compact is seen as essential. But how should this consolidation take place?

Kato and other researchers split the 20-kilometer area around Nagoya Station into 500-meter blocks, and evaluated them using three indicators: environmental footprint (CO2 emissions), cost of town maintenance for things like clean water and sewer services, and quality of living environment influenced by factors such as transportation convenience and safety against disasters. They identified areas where environment quality was low in relation to maintenance costs, essentially low-efficiency areas, and deemed them "retreat" districts where people are encouraged to leave. Moving the residents from these districts to areas with better efficiency would make it possible at a minimal cost to maintain overall quality of life, or even improve it.

Looking at those results, many of the "retreat" districts are located on the western side, where there are many zones of sub-sea level land. Yet development around Nagoya Station has resulted in a higher level of convenience in this western area compared to before, and the population there tends to grow instead. Kato says that it is necessary to share as much information of this kind as possible, and make cities more compact while discussing if measures are to be taken so that people can continue living there, or if they would be encouraged to leave.

Professor Hirokazu Kato, Graduate School of Environmental Studies

Professor Hirokazu Kato, Graduate School of Environmental Studies

Considering the tough state of public finance, we must not forget the costs being paid to live in dangerous locations -- so says Visiting Professor Masayuki Takemura of the Disaster Mitigation Research Center. For example, sub-sea level zones are protected by constantly running water removal pumps, and by maintaining functioning tide gates.

Takemura is researching the effects of the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake and other past major earthquakes using records like stone monuments. At Susaki Shrine in Kiba, Koto City -- an area known for being in the sub-sea level zone of Tokyo Bay -- he found a stone namiyoke (avoiding sea water)marker. At the end of the 18th century, high tides swept away homes and left behind many victims, so the Tokugawa shogunate bought the entire area and erected stone markers, prohibiting people from living anywhere between them and the sea. The government had determined that, rather than enact countermeasures, it made more financial sense to buy the land and have residents move away. The land was then used to farm medicinal plants. The Meiji government cancelled the Tokugawa policy when they came into power, and people moved back as they were protected by the embankments, yet Takemura says the shogunate's concept is indeed necessary today.

Upon researching the recovery after the 1923Great Kanto Earthquake, there were also some things that he admired. "Now is the time" had become a popular phrase in those days. Based on the major policy of Imperial City Restoration Department President Shinpei Goto, the general public was persuaded to hand over their land for town planning, which was used to create infrastructure like wide roads and memorial parks near elementary schools. There were of course complaints, but Takemura thinks that city residents supported the plan because they thought, now is the time to create something that lasts, something they can be proud of in 100 years. These roads and parks became main streets and metropolitan parks, and formed the basis of the Tokyo we know today. Over the Sumida River, bridges were constructed with the conditions that they "not be an eyesore, not break, and be grand," and they stayed standing and saved lives even during the air raids of World War II.

Speed is also demanded in recovery, and Takemura is astonished that they were able to create things with such care under those circumstances. It was a valuable use of money for the future. He says this is a major difference with the reconstruction after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami.

It would be no surprise if, at any time, a typhoon more powerful than the Isewan Typhoon were to hit. Had the courses of typhoons Faxai and Hagibis in 2019 been slightly different, they could have directly hit Tokyo's sub-sea level zone. The same goes with Aichi Prefecture, which has the largest sub-sea level zone in Japan. Takemura says it should be questioned how long taxpayer money is to be used protecting these areas.

In flood-prone countries like Germany and the Netherlands, there has been a move to prohibit construction in flood-prone areas or make the ground floors of buildings into parking and have people live on higher floors, rather than build higher embankments. Doing so allows money that would have been spent on flood defense to be used for other purposes.

Dean Norimi Mizutani of the Graduate School of Engineering specializes in civil engineering, and says that, in addition to disaster risk reduction, an objective of land design is to also comprehensively consider where and how in cities and rural areas people can live comfortably and efficiently, in order to position towns in a way that utilizes merits of each area. How do we live on this disaster-prone land? To figure this out, it is necessary to think with both a long-term vision and from various viewpoints.

A warning written on a stone pillar, erected in front of the namiyoke marker at Susaki Shrine in Kiba, Tokyo. After the high tide disaster in 1791, the Tokugawa government bought up and evacuated the area, and erected two markers at its edge.

A warning written on a stone pillar, erected in front of the namiyoke marker at Susaki Shrine in Kiba, Tokyo. After the high tide disaster in 1791, the Tokugawa government bought up and evacuated the area, and erected two markers at its edge.

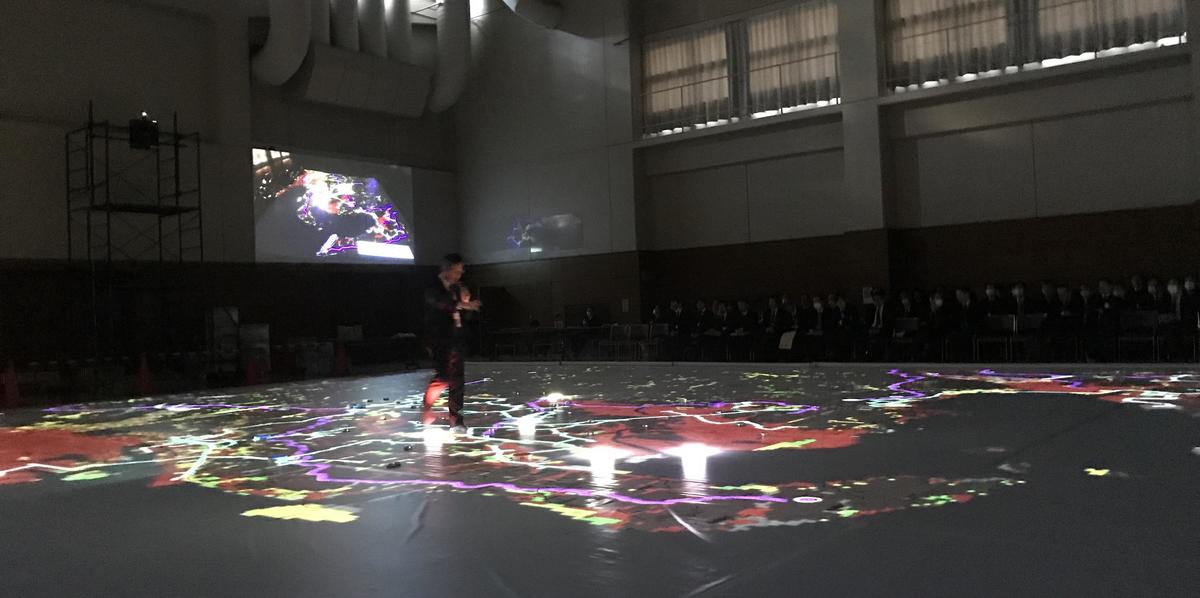

Such design should of course consider each region carefully, and ideas that transcend borders are necessary. As there are now fears of a major disaster, the first issue is allowing towns located in dangerous areas to sustain. To make this possible, Director Nobuo Fukuwa of the Disaster Mitigation Research Center is engaged in unprecedented trials throughout the country, devising partnerships that cross the borders of regions and industries. The Nishi-Mikawa region is formed by nine cities and one village, and stretches across the center of Aichi Prefecture from Toyota City to Nishio City. It is a major industrial area that centers on automotive production, and ships around 25 trillion yen worth of products each year -- 8.3% of the national total. As cooperation is essential for a quick recovery in times of disaster, Fukuwa led the establishment of the Nishi-Mikawa Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Coordination Committee. At a workshop held at the end of January 2020, there were around 120 participants, including from the prefectural government and related companies. As water was the theme for this session, a map showing the location of water pipes was displayed across the entire gymnasium floor using projection mapping, and participants discussed the feasibility of anticipated recovery and potential challenges.

On the other hand, monthly meetings called Honne no Kai (honest opinions meetings) have been held, where representatives from around 100 organizations, including local municipalities and companies related to the automotive, energy, and gas industries, discuss their frank opinions about disaster risk reduction under a pact of non-disclosure. The results of these meetings in the Nagoya area have been successful, and in the future Fukuwa hopes to expand the initiative among industry organizations and to other regions like Tokyo. This year, exactly 20 years of his networking with media organizations has led to the unprecedented agreement between TV stations to cooperate in helicopter filming during disasters.

Crossing borders between different fields with a focus on disaster risk reduction -- what could be called the Nagoya model -- will undoubtedly be a great strength in working towards building a resilient society.

At the Nishi-Mikawa Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Research Committee workshop, participants spoke while walking on a map projected across the entire floor. (January 31 at the Nishio City Gymnasium)

At the Nishi-Mikawa Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Research Committee workshop, participants spoke while walking on a map projected across the entire floor. (January 31 at the Nishio City Gymnasium)

On a final note, going back to the Isewan Typhoon, I want to share something one of my senior colleagues told me when I was still a cub newspaper reporter. One week after the disaster, as my colleague choked back tears while reporting from the sea of mud, a famous veteran reporter arrived from Tokyo. That veteran reporter took a single boat ride around the area, then returned home. My colleague wondered what on earth he could write about after just that short trip, but was shocked upon reading the article.

That famous reporter was Keiichiro Hikita, one of the most prominent post-war newspaper journalists, who was known for his relentless pursuit of the mission and essence of journalism. He always took a hard look at himself as well. Hikita had written that "the machines remained." In essence, a factory that had been built somewhere up high was not flooded, but the surrounding homes were submerged in muddy water. My colleague felt as if "I was looking, but I wasn't really seeing." Reflecting back, he also realized that he had simply been writing the national and local governments' party line that it was an "unavoidable incident" without questioning it.

In that article, Hikita wrote that the most unbearable part of walking in the affected area was Nagoya City. He questioned "why 1,600 residents had to become trapped and die," and if the overall urban planning hadn't been overly optimistic. He wrote that while "Nagoya City chose economic prosperity over uneconomic safety", it wasn't only the problem of Nagoya. "All of Japan is marching quickly and overstretching itself for development and prosperity", he said, concluding that, "it seems the new form of urban disaster has clearly revealed itself today in Nagoya." (from an article on the October 9, 1959, Asahi Shimbun).

Different people can see the same things in different ways. This is also probably true with research, which is exciting and challenging at the same time.

The Japanese archipelago is rich in the treasures of nature. But sometimes that nature shows us its fangs -- and those teeth are getting sharper. How do we live in harmony with that nature? Such a debate requires a long-term vision and diverse views. I believe providing these is certainly the duty of a university.

Subscribe to RSS

Subscribe to RSS