June 6, 2019

The University Team Behind Hayabusa2

The asteroid explorer Hayabusa2 of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) will attempt to make a second touch-down on the asteroid Ryugu as early as the end of June. Ryugu is a small object about one kilometer in diameter, currently at a distance of around 270 million kilometers from the Earth, meaning it takes radio waves about 30 minutes to get there and back. Hayabusa2 has a main body of around one meter in size, with solar panels extending from it. After a journey of around three and a half years, it reached Ryugu in late June 2018. This small spacecraft carries with it the scientists' grand ambitions to trace back our roots to the origins of the solar system. This is a full-scale scientific exploration, learning from the experience of its predecessor, the original Hayabusa, whose nail-biting return to the Earth captured the public imagination. A team of about 300 scientific researchers from universities all over Japan have worked together on Hayabusa2. Professor Sei-ichiro Watanabe of the Graduate School of Environmental Studies at Nagoya University is leading the team as Project Scientist. He appeared at a press conference at Meidai at the end of April, along with lecturer Tomokatsu Morota (now Associate Professor, Faculty of Science, the University of Tokyo, since May 2019) who played a major role in selecting landing sites. Watanabe said, "This is a complex and difficult mission, but working together with researchers from many universities, we are already seeing scientific achievements, including some surprising discoveries." I want to focus on the university team supporting the Hayabusa2 mission.

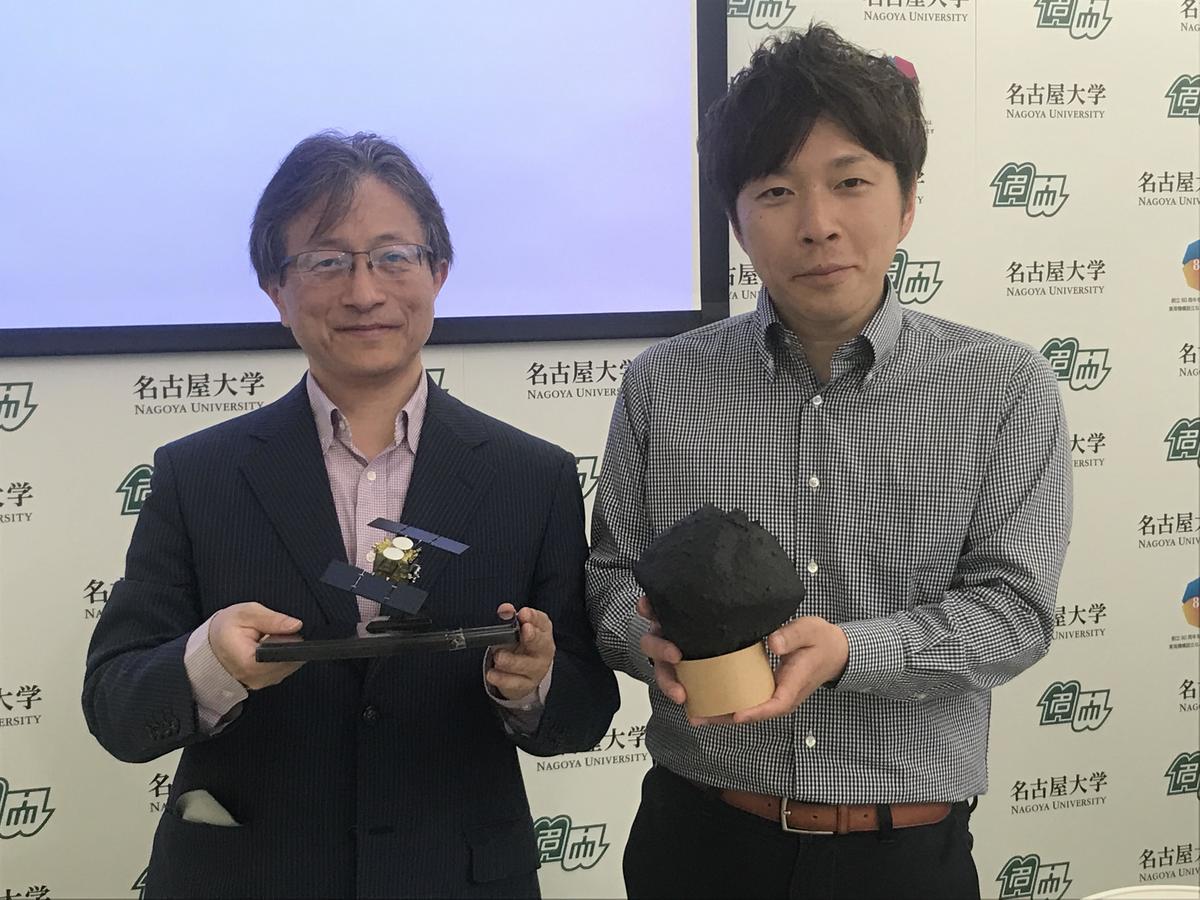

Professor Sei-ichiro Watanabe (Left) holding a model of Hayabusa2, and lecturer Tomokatsu Morota (now Associate Professor, the University of Tokyo) holding a model of Ryugu.

Professor Sei-ichiro Watanabe (Left) holding a model of Hayabusa2, and lecturer Tomokatsu Morota (now Associate Professor, the University of Tokyo) holding a model of Ryugu.

Asteroids are countless small astronomical objects orbiting the sun between Mars and Jupiter. Whereas the insides of large planets like the Earth have been melted by heat, asteroids are believed to have remained unchanged since they were formed, making them fossils of the solar system, so to speak. This means they hold clues about the time when our solar system was formed, around 4.5 billion years ago. As well as sending spacecraft to explore what asteroids are like, the purpose of asteroid exploration is to bring back samples of rock which can be analyzed to investigate the origins of our solar system.

The main objective of the first Hayabusa mission was to verify the technology enabling it to reach an asteroid, explore its surface, collect samples and bring them back to earth. Although it achieved a world first by landing on the asteroid Itokawa and then taking off again, the exploration on the asteroid's surface was not completely successful, and Hayabusa encountered several problems on its return to earth, including engine failure and a temporary loss of communication that meant it was effectively lost for some time. However, it overcame such desperate state with these difficulties and made it back to the Earth. In a dramatic finale, the capsule containing fine particles of dust from Itokawa was released and sent back to the Earth, while the spacecraft itself burnt up on re-entry. This gripping story was made into three feature films.

It's rather ironic that if Hayabusa had made it back to the Earth without any trouble, it might not have attracted so much attention.

This time, the mission has so far gone almost entirely to plan.

Hayabusa2's Mission Manager, Associate Professor Makoto Yoshikawa of JAXA, was also at the press conference. When asked "What was the hardest part?", he replied, "The hardest thing was getting funding." He had a hard time as Hayabusa failed in some procedures to collect samples and finally got funding for Hayabusa2 only after Hayabusa made it back to the Earth. Once the project began, everything has gone smoothly. In December 2018, Yoshikawa was selected as one of the "2018 Nature's 10" by British science journal Nature, in anticipation of achievements like touching down on the asteroid.

Hayabusa2 first touched down on the surface of Ryugu in February this year, when a projectile was fired out according to plan, and particles are believed to have been successfully collected in the capsule. In April it also succeeded in creating a world's first artificial crater on the surface of Ryugu by shooting an impactor of copper sphere to hit the surface, in order to investigate the inside of the asteroid. The second touch-down will aim for the area around this crater. If successful, it should be able to collect rock from inside the asteroid, exposed by the collision.

Hayabusa2 has also deployed a MINERVA-II rover which moves around by hopping, and a lander called MASCOT, jointly developed by the German and French space agencies. These both landed successfully on the surface of Ryugu. MASCOT is equipped with various kinds of observation instrument, and it helped to determine the landing site for Hayabusa2 by examining the appearance of the surface.

This is a pretty ambitious exploration plan. In fact, since before the funding for Hayabusa2 was officially decided, there has been a debate among the planetary science research community about how to conduct the exploration. In the past, JAXA has led explorations, and university researchers have only been involved individually in aspects such as developing observation instrument. But this time, the whole community of researchers has been working together for the first time, treating this as a full-scale scientific mission.

The asteroids Ryugu (Left on the screen) and Bennu, shown at the press conference. Ryugu is shaped like a bead of a traditional Japanese abacus.

The asteroids Ryugu (Left on the screen) and Bennu, shown at the press conference. Ryugu is shaped like a bead of a traditional Japanese abacus.

Ryugu was selected for exploration because it is a C-type asteroid, containing carbon and water. Substances essential to life, including carbon and water which form organic matter, are thought to have fallen to the Earth in the form of meteorites and so on. Many of the meteorites which have fallen to the Earth are also around 4.5 billion years old, and are believed to have come from asteroids breaking up. In other words, detailed study of asteroids will tell us about the origin of life on the Earth 4.5 billion years ago.

The main purpose of this exploration is to find out how organic matter and water exist in space, and how they came to reach the Earth by using asteroid fragments as a clue, and investigating their internal strength by collision tests.

So far, observations have shown that Ryugu is made up of debris that came together when the parent planet broke up, rotating at high speed to form a shape like a spinning top or abacus bead, which came as a surprise to the researchers. As the composition has become clearer, the mystery has deepened. "I am looking forward to analyzing the samples of the rocks that Hayabusa2 should bring back," says Watanabe.

Meanwhile, NASA's asteroid explorer OSIRIS-REx, launched two years after Hayabusa2, is exploring another C-type asteroid, Bennu, which is about half the size of Ryugu. Observations so far have produced very interesting results, showing that the two asteroids are very similar, with about the same density. It is very meaningful to study multiple subjects of the same type, investigating the similarities and differences and finding out what they mean. The result of "one plus one" is sure to be more than two.

This unprecedented close collaboration with NASA, as well as with the German and French space agencies in charge of the lander, is another feature of this project. Just like the observation of black holes, solving huge mysteries requires international collaboration.

One of the themes on which NASA required cooperation to Hayabusa2 was the landing. Without going to the site and investigating in detail, it is impossible to know where a spacecraft can land safely. "First Man", the biographical movie about Neil Armstrong, shows how Apollo 11 reached the moon but struggled to find a suitable place to land, finally finding a landing site just as it was about to run out of fuel.

When Hayabusa2 reached Ryugu it found the surface was rocky. "Ryugu has finally bared its teeth," said Project Manager Yuichi Tsuda, as the planned landing was postponed.

Is there anywhere to land safely on such a rocky surface? As deputy chief of the optical navigation camera team, Tomokatsu Morota played a central role in selecting a suitable site. After selecting a target area of three meters in radius, he calculated the height of all 400 or so rocks within this range, from the length of their shadows. To ensure Hayabusa2's leg would not catch, there had to be no rocks more than 65-centimeter high. Morota identified a site near a rock 52-centimeter high. Of course, there is an error of a few centimeters. Hayabusa2 landed safely, with an accuracy equivalent to landing on the baseball mound of Koshien Stadium from a height of 20 kilometers. The photographs show a rock 52-centimeter high, named Death's Rock, right next to the leg. "I was relieved that my estimate was correct," admits Morota.

But what an amazing contrast: a matter of a few centimeters, 270 million kilometers away.

Seeing these achievements of the Hayabusa2 mission, I feel I should be ashamed of my own past lack of insight. In 2001, when I was a newspaper reporter, an asteroid discovered by an amateur astronomer was given my name: asteroid 8414 "Atsuko." Amused by this, my boss asked me to write an article for the science section of the newspaper, called "How I Became a Star." I ended the piece: "I look forward to the day when a spacecraft from NASA will come and visit the asteroid Atsuko." At that time, NASA was the space agency known for exploring other planets, with its Voyager program as a centerpiece. NASA also launched an asteroid explorer called NEAR in 1996.

It was only a few years after that, in 2003, when Hayabusa was launched. Now, JAXA's asteroid explorer has overtaken NASA to become a reliable presence.

I spent three years in Washington as a science correspondent until early 2000. Daniel Goldin, the head of NASA at that time, brought in a new policy of "faster, better, cheaper", in contrast to the huge programs of the past, like Voyager. NASA started to focus on small, inexpensive probes and satellites, and launching them quickly. NEAR was the first of a series of such missions called the Discovery Program.

This "faster, better, cheaper" approach was said to be modeled on the scientific satellites and explorations of the Japanese Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS, now part of JAXA). Due to budget constraints, researchers were involved in both design and observation, and significant results were achieved with relatively inexpensive astronomy satellites especially in the field of X-ray observation.

Twenty years later, the eyes of the world are on Hayabusa2, which has come a long way since those days. Now, Morota and the rest of the team are once more looking for a landing site near the crater. Hayabusa2 should touch down by early July, and by the end of this year it will bid farewell to Ryugu, where it will have spent a year and a half. It will return to the Earth in late 2020. I am looking forward to the day when we see the true face of Ryugu, an asteroid that Morota says is "even more interesting than we imagined." And perhaps one day, JAXA will send a spacecraft to visit the asteroid Atsuko.

Subscribe to RSS

Subscribe to RSS